You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ravenna, the midwife of Europe

- Thread starter AndreaConti

- Start date

First of all, he continues to be bishop of the diocese of Aeclanum, he will not be deposed (among other things, Aeclanum will never be abandoned, as a city) and he will continue to dedicate himself to theology: if his controversy with Augustine will be less harsh, however, unlike OTL, he will argue heatedly with Nestorius, accusing him of being crypto-Aryan. Upon his death, he will be venerated as a saint by the Nicean ChurchGreat updates! It is written in the life of St Genevieve that the man of Pelagius was created by the Christ of Nestorius, so there was apparently a connection that their contemporaries saw. On that note, what is Julian of Aeclanum doing TTL?

Are there any Roman Arians in TTL or is as in OTL an ethnic marker for the Goths/Vandals, etc?

No, compared to OTL the dimension of Arianism as a tool for building an ethnic identity will be less present: Roman Aryans will continue to exist, who will have something to do with the church of Mediolanum

39 The Days of Britain

39 The Days of Britain

In the first half of the 4th century, despite the restless neighbors and the resurgences of independence, Britain was now an integral part of the Empire and could boast a population estimated at around 1,500,000 inhabitants and wealth due to flourishing agriculture [1]: this period of economic growth entered in crisis during the reign of Valentinianus I, due to the Emperor's greater attention to the events of the Rhenish and Danubian Limes. Given Rome's inattention, corruption triumphed: if the imperial officials filled their pockets with the tax proceeds directed to the treasury, while the Roman generals kept for themselves the money sent to pay the troops, generating the discontent of the soldiers who, poorly paid, they soon began to desert en masse. To make everything worse, from 360 onwards Britain, Caledonia and Hibernia are plagued by terrible agricultural years: on the one hand, there are a series of continuous peasant revolts, which although not reaching the levels of the Bagaudes, further weaken the the Roman authority, on the other the Caledonians, driven by hunger, suspend the internal struggles between them and break through the limes, bringing chaos to the British provinces, also because, the aforementioned corruption, the subsidies coming from the Empire, on which it was based their economy, had been suspended, ending up in the pockets of Roman officials.

Valentinianus, realizing with guilty delay the chaos that was unleashing, which Ammianus Marcellinus exaggeratedly attributes to a sort of conspiracy, the barbarica conspiratio, [2] commissioned the comes Theodosius, the grandfather of Honorius and Galla Placidia, to restore a sort of order in the restless province, suppressing rebels and invaders, who were little more than gangs of hungry marauders, repairing both civil and military infrastructure and replenishing the ranks of local garrisons, inviting deserters to return to service, promising them not only forgiveness and payment of the salary arrears due, but also of the incentives; the measure was successful, as many of the deserters, trusting in forgiveness and encouraged by the advantages, actually returned to service. [3]

Although Claudianus, who acted as Honorius' court poet, even though the emperor could hardly stand him, writes

debellatorque Britanni

litoris ac pariter Boreae vastator et Austri.

quid rigor aeternus, caeli quid frigora prosunt

ignotumque fretum? maduerunt Saxone fuso

Orcades

Scottorum cumulos flevit glacialis Hiverne. [4]

Theodosius the Elder's successes are transitory. In 407 the legions of Britain acclaim as emperor Constantinus III, who crossed the Channel but was defeated by the troops of the legitimate Western emperor Honorius. It is not known, after this event, how many Roman troops actually remained in Britain. In 408 a Saxon incursion was apparently repelled by the local population and from 409 onwards, Britain, until the arrival of Exuperantius, was effectively left to itself by Ravenna. All events which certainly did not favor the economic growth of the province: however, things changed rapidly for the administration of Quintu Fabius Memmius Simmacus, who launched a series of public works and fought corruption with exemplary rigor, the military successes of Flavius Egnatius Mavortius, who bring peace to the frontiers and trade of the Suebi. Factors that rapidly change the province's economy. Thanks also to the investments of the Suebi and the great Roman senatorial families, the extraction activity of the British mines was greatly relaunched.

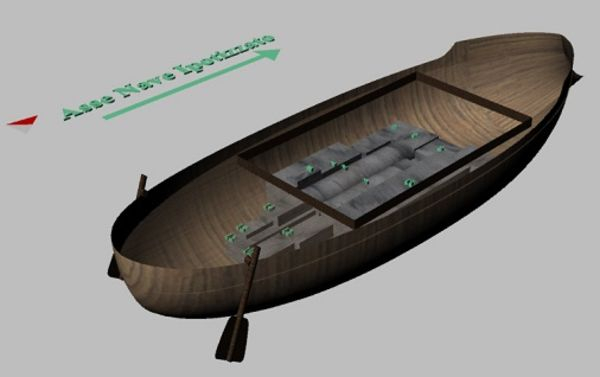

The Mendipius mines [5] have something of a boom; the lead that is extracted there, in addition to traditional uses, the pipes of the aqueducts, is highly sought after by the Suebi, who use it to protect the keel and planking of ships from shipworms, according to what Anicius Severus tells us. Evidence confirmed by underwater archaeology: the keels of Suebe ships are protected by a lead sheet fixed with copper nails, and a waterproofing layer of wool felt soaked in pitch is inserted between the sheets and the wood. [6] This boom was also favored by the progressive exhaustion of its main competitors, the Iberian mines.

Since lead is extracted from galena in Mendipius, the growth in the extraction of this mineral has also led, through cupellation, to an increase in the extraction of silver. At the same time, the cultivation of the gold mines of Luentinum [7]has expanded and about ten new iron mines have been opened; but the big news of the fifth century in Britain was the start of extensive extraction of fossil coal both to fuel the forges for the extraction of silver and the processing of iron, wood coal being more efficient as a fuel, and for the increased heating needs, due to climate change, and, what has been realized in recent years, for its progressive use, together with gum arabic, for the production of inks [8]

In parallel, as a consequence of lower agricultural productivity, the fields are transformed into sheep pastures, which causes a rapid growth in wool production, which causes the birth and development, thanks to the greater demand always due to the decrease in average temperatures, of a textile industry: from what archeology has managed to reconstruct, the main collection point for raw wool was Eburacum: [9] from there British merchants brought it to Durovernum Cantiacorum, [10] where numerous factories were born, in the area of the Roman theatre, where rough cloths were woven, in turn transported to Londinium,[11] in whose port they were purchased by Suebi merchants, who brought them home to dye and resell them.

A further factor of change in the economy of Britain is the development of maritime trade, again due to the Suebi; the ports of Anderida, Portus Lemanis, Dubrae, Rutupiae and Regulbium are expanded and Londinium has notable urban growth, passing in a few years, as evidenced by archeology from 30,000 to 50,000 inhabitants, something which in April 428 is also testified by Flavius Aetius , which decides to formalize, with the approval of Ravenna, the status of the Londinium mint, whose activity is not only officially recognized, but is strengthened with the sending of argentarii from Arleate, to improve and regularize the minting of coins silver, increasingly necessary to support economic growth.

The other side of the coin, however, is the continuous depopulation of the countryside, which has two unexpected administrative and demographic impacts. Now, when Honorius and Exuperantius had decided, in order to keep Britain's elites happy and put an end to their secessionist attempts, to create a Concilium Britanniae, similarly to what was done in Gaul, they took it for granted that power remained in the hands of the large landowners : the unexpected economic changes, however, caused their importance to decrease in favor of a class of "homines novi", often of Celtic origin or poorly romanised, who however were enriching themselves thanks to their business with the Suebi and the Roman senators. Therefore, Flavius Aetius, in June 428 decreed a change in the composition of the Concilium Britanniae, which, in addition to the representatives of the curiales, who were regaining importance, were also joined by those of the collegia.

At the same time, Flavius Aetius must keep the landowners good, who have difficulty finding colonists to cultivate their estates and cannot resort to purchasing slaves from Hibernia, mostly headed to Hispania: for this reason, he authorized in the autumn of the same year, the entry of Laeti from Germania Magna and from the land of the Dani. According to the account of Anicius Severus, these immigrants were essentially Saxones, Jutes, settling in southern Britain, and the Angles. An indication which is also confirmed by the venerable Bede, [12]who instead lists these peoples: Fresones, Rugini, Danai, Hunni, Antiqui Saxones, Boructuarii.

Immigration which has a double impact: on the one hand thanks to them the agricultural landscape changes, with the spread of the cultivation of rye and oats, on the other thanks to the spread of the phenomenon of seasonal laborers or tenants, who once their contract expires, they return to Scantinavia or Germania Magna, contributing to changing Saxon and Northern European society. This immigration, unlike what happened in 406, occurs at the level of individuals, families and clans and not of organized peoples, and is the cause of the complex linguistic pluralism of Britain, which is demonstrated by the double and sometimes triple toponymy of that region. The best-known examples of this multiple denomination are: Venta Icenorum, which the Angles and Saxons call Cæster ("Roman fort"), Deva Victrix or Legacæstir ("city of the legion"); Noviomagus Reginorum or Cicæstre (Cissa fortress), Corinium or Cirencæster, Colonia Camulodunum or Colencæster, Uueogorna civitas or Weogorna cæstre, Venta Belgarum or Wintancæstre.

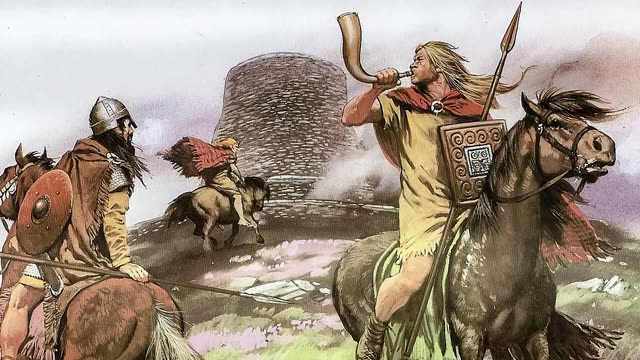

Furthermore, since the immigrants were mostly pagans, the problem also arose in Rome and Arleate of who should evangelize them and how. These changes also had an impact north of the Vallum Hadriani, starting with the Picts, a name in which, in the second half of the 4th century, imperial historians and geographers began to identify a group of Caledonian tribes, who spoke a Celtic language very similar to that of the peoples of Roman Britain, who like their southern relatives, were farmers living in small villages. [13]

Cattle and horses, the possession of which, according to Anicius Severus, was a monopoly of the Pictish nobility, which based its prestige on the number and size of the cattle it owned: disputes over the herds were the cause of feuds which have been the subject of songs and sagas.

If the pigs, according to the testimony of the venerable Bede, were the property of the villages, whose inhabitants raised them in common and distributed the meat according to the number of members of the individual families, the flocks of sheep were the property of the King, who used slaves from Hibernia as herders. The nobility also practiced falconry: something also testified by Anicius Severus, who tells how Theodosius III, a great hunting enthusiast, commissioned a treatise on falconry from a presbyteros of Pictish origin

De arte venandi cum avibus [14]

of which a fragment of the introduction remains, which due to its "philosophical" contents was perhaps written by a Roman intellectual who frequented the circle of his brother Valentinianus

In writing we also followed Aristotle, when this seemed necessary. In some places, however, We are of the opinion, based on the experiences We have conducted, that, as regards the nature of certain birds, he has departed from the truth. Therefore we do not entirely agree with the Prince of philosophers since he never or only rarely dedicated himself to falconry, unlike Us who have always loved and practiced it. Aristotle narrates many things about animals specifying that others said them; but what others claimed, he himself neither saw nor was seen by those who vouched for him. Certainty is not achieved by quoting what others have said, but by concrete experience. [15]

Topics that were probably not known or debated among the Picts. Their agriculture included wheat, barley, oats and rye, the introduction of which to this day is believed to predate and be independent of the arrival of the Anglo and Saxon immigrants: vegetables included cabbage, kale, onions, leeks and garlic, of which according to Bede the Picts they were great lovers, peas, beans and turnips and others not widespread south of the Vallum Adriani such as the skirret, nettle and watercress. An equally important role in their economy was played by fishing and shellfish gathering.

Until the time of Theodosius the Elder, they lived in tribes independent of each other: however, in the troubles between the end of the 4th century and the beginning of the 5th century, two warlords, whom the local sagas call Gartnait and Talorc, succeeded with the force to reunify them, founding a kingdom called Uerteru and which the Roman chronicles define as Verturiones. In January 429, from the stories of Anicius Severus, one of their embassies, sent by a king called Driestus, coinciding with the Drest of the Pictish Chronicle, arrived in Ravenna.

Driestus, in addition to defining himself as Socius et amicus populi Romani, [16] asked for three things in the embassy. The first, a reduction in customs duties on Pictish wool bound for Eburacum, which must have constituted an important item in his personal income. The second, the sending from Rome of a bishop who would organize the church of his kingdom, testifying to the fact that an important component of the Pictish population had to be Christianized. Finally, Rome's request to mediate a dispute with an ambitious neighbor, which is the first historical testimony of Dal Riata's reign; an ambitious adventurer, whom the Hibernian chronicles call Eochaid Muinremuir, whom Anicius Severus Latinizes into Eugenius, and who was a cousin or nephew Niall Noigíallach had enlisted a contingent of Alan mercenaries, Goths and Roman veterans, conquering Ulster; not having satisfied his ambitions and not wanting either to fight against his relatives or against the Empire, he had invaded the coast of Caledonia, occupying the Airer Goídel and coming dangerously close to the dominions of Driestus.

Galla Placidia probably had very confused ideas about where those places were, however, given the experience of her family, she was aware of one thing: any war in Caledonia would sooner or later cause big trouble in Britain. So, having reduced the duties on the wool of the king of the Picts, in March 429, she commissioned Flavius Aetius to send an embassy to Eugenius, who was ambitious, but certainly not stupid. The adventurer, not wanting to have problems with the Empire, agreed to establish precise borders with the Verturiones and according to what Anicius Severus tells, to strengthen the agreement he married the youngest daughter of Driestus.

[1] Based on the estimates that are most popular among Italian scholars

[2] Barbarians' plot

[3] There is something of a historiographical mystery about the extent of Valentia: given the latest archaeological discoveries in Stirling, it probably extended further north than previously assumed.

[4] He subjugated the coasts of Britain and with equal success devastated the North and the South. Could the eternal snows, the freezing air, the unknown seas ever stop him? The Orkneys became red from the massacre of the Saxons and the same happened to Thule from the massacre of the Picts]; glacial Ibernia wept over the heap of massacred Scots.

As it often happens. Claudianus exaggerates with enthusiasm

[5] Mendip Hills, Somerset

[6] Inspired by real 5th century ships

[7] Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire

[8] Which is how OTL also happens

[9] York

[10] Canterbury

[11] London

[12] That ITL will exist

[13] Based on the theories of Italian scholars

[14] The references to Frederick II of Swabia are purely coincidental

[15] Quotation from Frederick's treatise

[16] Friend and ally of the Roman people

In the first half of the 4th century, despite the restless neighbors and the resurgences of independence, Britain was now an integral part of the Empire and could boast a population estimated at around 1,500,000 inhabitants and wealth due to flourishing agriculture [1]: this period of economic growth entered in crisis during the reign of Valentinianus I, due to the Emperor's greater attention to the events of the Rhenish and Danubian Limes. Given Rome's inattention, corruption triumphed: if the imperial officials filled their pockets with the tax proceeds directed to the treasury, while the Roman generals kept for themselves the money sent to pay the troops, generating the discontent of the soldiers who, poorly paid, they soon began to desert en masse. To make everything worse, from 360 onwards Britain, Caledonia and Hibernia are plagued by terrible agricultural years: on the one hand, there are a series of continuous peasant revolts, which although not reaching the levels of the Bagaudes, further weaken the the Roman authority, on the other the Caledonians, driven by hunger, suspend the internal struggles between them and break through the limes, bringing chaos to the British provinces, also because, the aforementioned corruption, the subsidies coming from the Empire, on which it was based their economy, had been suspended, ending up in the pockets of Roman officials.

Valentinianus, realizing with guilty delay the chaos that was unleashing, which Ammianus Marcellinus exaggeratedly attributes to a sort of conspiracy, the barbarica conspiratio, [2] commissioned the comes Theodosius, the grandfather of Honorius and Galla Placidia, to restore a sort of order in the restless province, suppressing rebels and invaders, who were little more than gangs of hungry marauders, repairing both civil and military infrastructure and replenishing the ranks of local garrisons, inviting deserters to return to service, promising them not only forgiveness and payment of the salary arrears due, but also of the incentives; the measure was successful, as many of the deserters, trusting in forgiveness and encouraged by the advantages, actually returned to service. [3]

Although Claudianus, who acted as Honorius' court poet, even though the emperor could hardly stand him, writes

debellatorque Britanni

litoris ac pariter Boreae vastator et Austri.

quid rigor aeternus, caeli quid frigora prosunt

ignotumque fretum? maduerunt Saxone fuso

Orcades

Scottorum cumulos flevit glacialis Hiverne. [4]

Theodosius the Elder's successes are transitory. In 407 the legions of Britain acclaim as emperor Constantinus III, who crossed the Channel but was defeated by the troops of the legitimate Western emperor Honorius. It is not known, after this event, how many Roman troops actually remained in Britain. In 408 a Saxon incursion was apparently repelled by the local population and from 409 onwards, Britain, until the arrival of Exuperantius, was effectively left to itself by Ravenna. All events which certainly did not favor the economic growth of the province: however, things changed rapidly for the administration of Quintu Fabius Memmius Simmacus, who launched a series of public works and fought corruption with exemplary rigor, the military successes of Flavius Egnatius Mavortius, who bring peace to the frontiers and trade of the Suebi. Factors that rapidly change the province's economy. Thanks also to the investments of the Suebi and the great Roman senatorial families, the extraction activity of the British mines was greatly relaunched.

The Mendipius mines [5] have something of a boom; the lead that is extracted there, in addition to traditional uses, the pipes of the aqueducts, is highly sought after by the Suebi, who use it to protect the keel and planking of ships from shipworms, according to what Anicius Severus tells us. Evidence confirmed by underwater archaeology: the keels of Suebe ships are protected by a lead sheet fixed with copper nails, and a waterproofing layer of wool felt soaked in pitch is inserted between the sheets and the wood. [6] This boom was also favored by the progressive exhaustion of its main competitors, the Iberian mines.

Since lead is extracted from galena in Mendipius, the growth in the extraction of this mineral has also led, through cupellation, to an increase in the extraction of silver. At the same time, the cultivation of the gold mines of Luentinum [7]has expanded and about ten new iron mines have been opened; but the big news of the fifth century in Britain was the start of extensive extraction of fossil coal both to fuel the forges for the extraction of silver and the processing of iron, wood coal being more efficient as a fuel, and for the increased heating needs, due to climate change, and, what has been realized in recent years, for its progressive use, together with gum arabic, for the production of inks [8]

In parallel, as a consequence of lower agricultural productivity, the fields are transformed into sheep pastures, which causes a rapid growth in wool production, which causes the birth and development, thanks to the greater demand always due to the decrease in average temperatures, of a textile industry: from what archeology has managed to reconstruct, the main collection point for raw wool was Eburacum: [9] from there British merchants brought it to Durovernum Cantiacorum, [10] where numerous factories were born, in the area of the Roman theatre, where rough cloths were woven, in turn transported to Londinium,[11] in whose port they were purchased by Suebi merchants, who brought them home to dye and resell them.

A further factor of change in the economy of Britain is the development of maritime trade, again due to the Suebi; the ports of Anderida, Portus Lemanis, Dubrae, Rutupiae and Regulbium are expanded and Londinium has notable urban growth, passing in a few years, as evidenced by archeology from 30,000 to 50,000 inhabitants, something which in April 428 is also testified by Flavius Aetius , which decides to formalize, with the approval of Ravenna, the status of the Londinium mint, whose activity is not only officially recognized, but is strengthened with the sending of argentarii from Arleate, to improve and regularize the minting of coins silver, increasingly necessary to support economic growth.

The other side of the coin, however, is the continuous depopulation of the countryside, which has two unexpected administrative and demographic impacts. Now, when Honorius and Exuperantius had decided, in order to keep Britain's elites happy and put an end to their secessionist attempts, to create a Concilium Britanniae, similarly to what was done in Gaul, they took it for granted that power remained in the hands of the large landowners : the unexpected economic changes, however, caused their importance to decrease in favor of a class of "homines novi", often of Celtic origin or poorly romanised, who however were enriching themselves thanks to their business with the Suebi and the Roman senators. Therefore, Flavius Aetius, in June 428 decreed a change in the composition of the Concilium Britanniae, which, in addition to the representatives of the curiales, who were regaining importance, were also joined by those of the collegia.

At the same time, Flavius Aetius must keep the landowners good, who have difficulty finding colonists to cultivate their estates and cannot resort to purchasing slaves from Hibernia, mostly headed to Hispania: for this reason, he authorized in the autumn of the same year, the entry of Laeti from Germania Magna and from the land of the Dani. According to the account of Anicius Severus, these immigrants were essentially Saxones, Jutes, settling in southern Britain, and the Angles. An indication which is also confirmed by the venerable Bede, [12]who instead lists these peoples: Fresones, Rugini, Danai, Hunni, Antiqui Saxones, Boructuarii.

Immigration which has a double impact: on the one hand thanks to them the agricultural landscape changes, with the spread of the cultivation of rye and oats, on the other thanks to the spread of the phenomenon of seasonal laborers or tenants, who once their contract expires, they return to Scantinavia or Germania Magna, contributing to changing Saxon and Northern European society. This immigration, unlike what happened in 406, occurs at the level of individuals, families and clans and not of organized peoples, and is the cause of the complex linguistic pluralism of Britain, which is demonstrated by the double and sometimes triple toponymy of that region. The best-known examples of this multiple denomination are: Venta Icenorum, which the Angles and Saxons call Cæster ("Roman fort"), Deva Victrix or Legacæstir ("city of the legion"); Noviomagus Reginorum or Cicæstre (Cissa fortress), Corinium or Cirencæster, Colonia Camulodunum or Colencæster, Uueogorna civitas or Weogorna cæstre, Venta Belgarum or Wintancæstre.

Furthermore, since the immigrants were mostly pagans, the problem also arose in Rome and Arleate of who should evangelize them and how. These changes also had an impact north of the Vallum Hadriani, starting with the Picts, a name in which, in the second half of the 4th century, imperial historians and geographers began to identify a group of Caledonian tribes, who spoke a Celtic language very similar to that of the peoples of Roman Britain, who like their southern relatives, were farmers living in small villages. [13]

Cattle and horses, the possession of which, according to Anicius Severus, was a monopoly of the Pictish nobility, which based its prestige on the number and size of the cattle it owned: disputes over the herds were the cause of feuds which have been the subject of songs and sagas.

If the pigs, according to the testimony of the venerable Bede, were the property of the villages, whose inhabitants raised them in common and distributed the meat according to the number of members of the individual families, the flocks of sheep were the property of the King, who used slaves from Hibernia as herders. The nobility also practiced falconry: something also testified by Anicius Severus, who tells how Theodosius III, a great hunting enthusiast, commissioned a treatise on falconry from a presbyteros of Pictish origin

De arte venandi cum avibus [14]

of which a fragment of the introduction remains, which due to its "philosophical" contents was perhaps written by a Roman intellectual who frequented the circle of his brother Valentinianus

In writing we also followed Aristotle, when this seemed necessary. In some places, however, We are of the opinion, based on the experiences We have conducted, that, as regards the nature of certain birds, he has departed from the truth. Therefore we do not entirely agree with the Prince of philosophers since he never or only rarely dedicated himself to falconry, unlike Us who have always loved and practiced it. Aristotle narrates many things about animals specifying that others said them; but what others claimed, he himself neither saw nor was seen by those who vouched for him. Certainty is not achieved by quoting what others have said, but by concrete experience. [15]

Topics that were probably not known or debated among the Picts. Their agriculture included wheat, barley, oats and rye, the introduction of which to this day is believed to predate and be independent of the arrival of the Anglo and Saxon immigrants: vegetables included cabbage, kale, onions, leeks and garlic, of which according to Bede the Picts they were great lovers, peas, beans and turnips and others not widespread south of the Vallum Adriani such as the skirret, nettle and watercress. An equally important role in their economy was played by fishing and shellfish gathering.

Until the time of Theodosius the Elder, they lived in tribes independent of each other: however, in the troubles between the end of the 4th century and the beginning of the 5th century, two warlords, whom the local sagas call Gartnait and Talorc, succeeded with the force to reunify them, founding a kingdom called Uerteru and which the Roman chronicles define as Verturiones. In January 429, from the stories of Anicius Severus, one of their embassies, sent by a king called Driestus, coinciding with the Drest of the Pictish Chronicle, arrived in Ravenna.

Driestus, in addition to defining himself as Socius et amicus populi Romani, [16] asked for three things in the embassy. The first, a reduction in customs duties on Pictish wool bound for Eburacum, which must have constituted an important item in his personal income. The second, the sending from Rome of a bishop who would organize the church of his kingdom, testifying to the fact that an important component of the Pictish population had to be Christianized. Finally, Rome's request to mediate a dispute with an ambitious neighbor, which is the first historical testimony of Dal Riata's reign; an ambitious adventurer, whom the Hibernian chronicles call Eochaid Muinremuir, whom Anicius Severus Latinizes into Eugenius, and who was a cousin or nephew Niall Noigíallach had enlisted a contingent of Alan mercenaries, Goths and Roman veterans, conquering Ulster; not having satisfied his ambitions and not wanting either to fight against his relatives or against the Empire, he had invaded the coast of Caledonia, occupying the Airer Goídel and coming dangerously close to the dominions of Driestus.

Galla Placidia probably had very confused ideas about where those places were, however, given the experience of her family, she was aware of one thing: any war in Caledonia would sooner or later cause big trouble in Britain. So, having reduced the duties on the wool of the king of the Picts, in March 429, she commissioned Flavius Aetius to send an embassy to Eugenius, who was ambitious, but certainly not stupid. The adventurer, not wanting to have problems with the Empire, agreed to establish precise borders with the Verturiones and according to what Anicius Severus tells, to strengthen the agreement he married the youngest daughter of Driestus.

[1] Based on the estimates that are most popular among Italian scholars

[2] Barbarians' plot

[3] There is something of a historiographical mystery about the extent of Valentia: given the latest archaeological discoveries in Stirling, it probably extended further north than previously assumed.

[4] He subjugated the coasts of Britain and with equal success devastated the North and the South. Could the eternal snows, the freezing air, the unknown seas ever stop him? The Orkneys became red from the massacre of the Saxons and the same happened to Thule from the massacre of the Picts]; glacial Ibernia wept over the heap of massacred Scots.

As it often happens. Claudianus exaggerates with enthusiasm

[5] Mendip Hills, Somerset

[6] Inspired by real 5th century ships

[7] Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire

[8] Which is how OTL also happens

[9] York

[10] Canterbury

[11] London

[12] That ITL will exist

[13] Based on the theories of Italian scholars

[14] The references to Frederick II of Swabia are purely coincidental

[15] Quotation from Frederick's treatise

[16] Friend and ally of the Roman people

Oh, Theodosius takes some inspiration from Frederick II? Well, hopefully he'll have a better relationship with the Roman bishop than his counterpart.

It also looks like the model of seasonal workers is not just a one-way street, with men from the empire going up to Ireland to do some soldiering for money. What, does the Roman army neither pay enough nor have enough work to do? The Roman army?

It also looks like the model of seasonal workers is not just a one-way street, with men from the empire going up to Ireland to do some soldiering for money. What, does the Roman army neither pay enough nor have enough work to do? The Roman army?

It also looks like the model of seasonal workers is not just a one-way street, with men from the empire going up to Ireland to do some soldiering for money. What, does the Roman army neither pay enough nor have enough work to do? The Roman army?

If you think about it, ignoring the phenomenon of deserters, which compared to OTL we can reasonably consider to be smaller, the discharge for honesta missio was obtained after 20 years of service and that for emerita missio after 24 years... If the age of enlistment it was 18 years old, according to Ammianus Marcellinus, but I suspect it could also be lower, at 40 years old a comitatenses was discharged: a percentage probably, as in every army, will have had their problems returning to civilian life and as a trained veteran (but this happens also OTL) will certainly have had the opportunity to live as a bodyguard or mercenary

Very interesting and well written chapter on post-410 ATL Britannia.

It is surely reasonable that while some form of military protection was restored, Britannia would have to be more autonomous and rely on the Roman-Britannic on the track of Gallia, Hispania and the same Italia, which makes me see, the four great western european... Provinces? Regions? Dioceses? Anyway, are taking form for now in the contest of the Roman Imperial perimeter, which is something we don't usually take for granted IMO, it would be indeed interesting how they further mold each other in the next years...

What is interesting, is to see how Britannia doesn't have - yet - a dominant city but more like a balanced minor urban system, even if London begins to push more by getting a mint, but I have the feeling the bishopric which would emerge more stronger and influential in Britannia will lead to the rise of an effective capital, unless of course some Barbarian power would settle as foederati (or dominator) in the island... Anyway, we will see if Londinium or other Britannic cities will become influential like Arelate for Gallia and Ravenna-Milan-Rome for Italy.

Also, is interesting to note how the West is beginning to rely more on its mineral sources for its own needs. Britannia is still on the fence and wouldn't bet safely for staying in the Empire in the next decades, but at least, is quite the progress from OTL 410!

It is surely reasonable that while some form of military protection was restored, Britannia would have to be more autonomous and rely on the Roman-Britannic on the track of Gallia, Hispania and the same Italia, which makes me see, the four great western european... Provinces? Regions? Dioceses? Anyway, are taking form for now in the contest of the Roman Imperial perimeter, which is something we don't usually take for granted IMO, it would be indeed interesting how they further mold each other in the next years...

What is interesting, is to see how Britannia doesn't have - yet - a dominant city but more like a balanced minor urban system, even if London begins to push more by getting a mint, but I have the feeling the bishopric which would emerge more stronger and influential in Britannia will lead to the rise of an effective capital, unless of course some Barbarian power would settle as foederati (or dominator) in the island... Anyway, we will see if Londinium or other Britannic cities will become influential like Arelate for Gallia and Ravenna-Milan-Rome for Italy.

Also, is interesting to note how the West is beginning to rely more on its mineral sources for its own needs. Britannia is still on the fence and wouldn't bet safely for staying in the Empire in the next decades, but at least, is quite the progress from OTL 410!

40 Censua

40 Censua

Beyond the events of Britain, the interests of Galla Placidia, in 428, were concentrated on a much more important and controversial issue, resuming an old idea of Honorius, that is, carrying out a census populi Romani atque Foederati, [1] which had become increasingly necessary due to social, demographic and economic changes that had occurred in the Empire in recent decades. The objective of the new census was to precisely quantify the imperial properties, about which Ravenna had somewhat confused ideas, the Roman properties and subjects, subject to taxation and military enlistment, and to understand how many laeti and foederati were actually established in the Empire, even due to the tendency of their comes, to minimize their economic and military commitments

According to Anicius Severus, Galla Placidia proposed this census to the Regency Council after the Christmas mass of 427; the main supporter of the proposal was for obvious reasons Questor thesauroum Flavius Iunius Quartus Palladius. However, the work on its organization proceeded quite slowly, as well as due to the opposition of the Roman senators, who feared that the objective of the census was to make their traditional tax avoidance practices more difficult, also due to a series of bureaucratic problems assignment of the task.

In fact, if Galla Placidia's objective was to assign the task to Palladius, given the needs of imperial finances, Flavius Constantius Felix, based on precedents, insisted on saying that it was the task of the Magister Officiorum to organize the census: in the end, to cut the head to the bull, a joint commission was organized, with representatives of both committees... Commission in which the representatives of Flavius Castinus also participated, both for the question of enlistments and because, knowing the landowners, someone could have reacted badly to the checks requested by the Ravenna administration.

After many and many discussions, in May 428, according to the majority of scholars, there is a minority that tends to move the date to August, shortly before the transfer of the imperial court for the summer holidays to Aquileia, an appropriate constitutio Principis [2] in which:

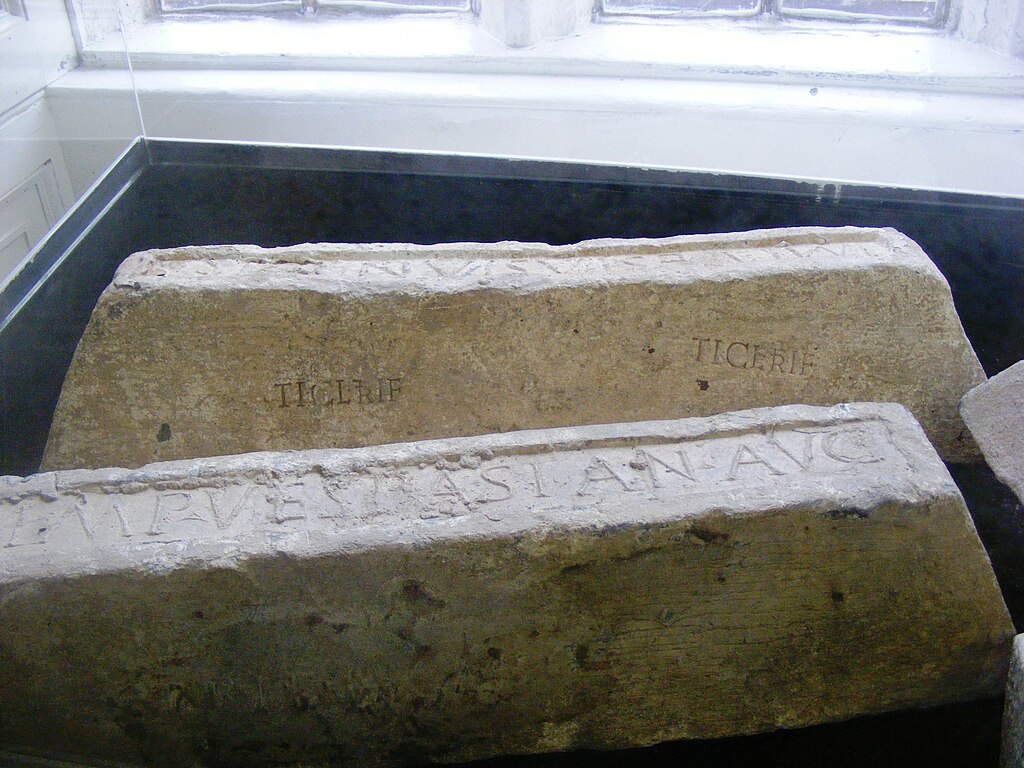

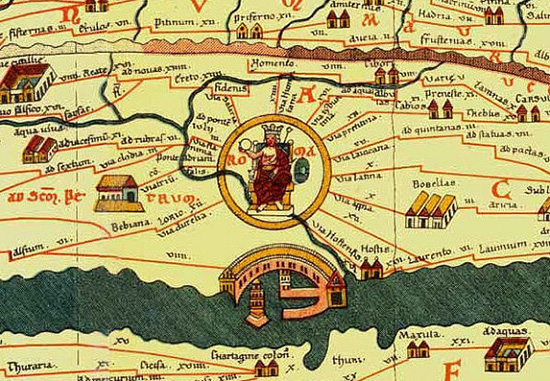

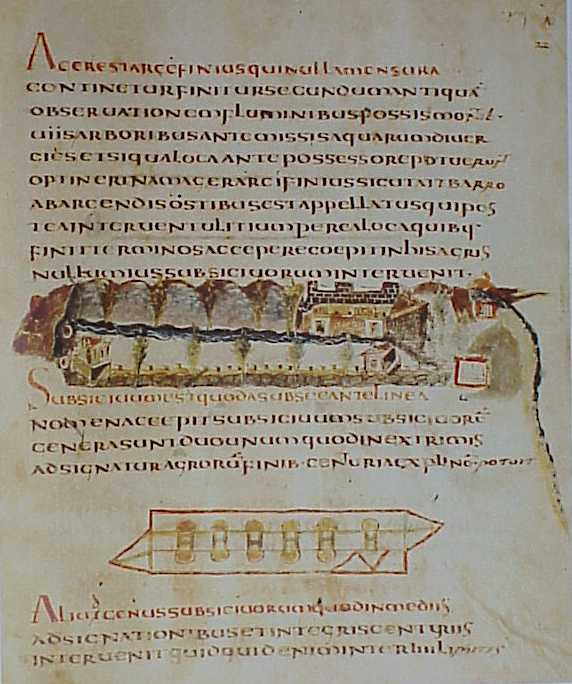

The first fact that immediately caught the scholars' eyes is how the distribution of the localities is similar to that of the Tabula Peutingeriana; therefore, it is probable that the initial nucleus of this document was a sort of annex to the Liber, to allow imperial officials to identify the locations to inspect; only later, perhaps at the beginning of the 6th century, was it expanded and transformed into an autonomous document, becoming a representation of the road and commercial connections of the world known to the Romans at the time. The chapters are also structured according to the practical indications contained in the Corpus Agrimensorum Romanorum; therefore the hypothesis was also put forward that this collection of technical treatises was somehow connected to the census verification operation. [6]

Chapters that are divided into three distinct sections: the first dedicated to the imperial property, the second to the properties of the cives, the third to that of the foederati. For pagus and large estates, the extent of arable land is evaluated with the number of ploughs, each with eight oxen, available to work it, plus any others available; then the meadows, olive groves, vineyards, orchards, woods, pastures, fish ponds, water mills, salt pans and other sources of collateral income are listed; the colonists, slaves and associated wage laborers are enumerated in their different categories; finally, the annual income of the entire property is expressed approximately. For cities, for each building the rooms, the inhabitants, the connected economic activities and the associated income are enumerated.

The text, written in a literary Latin that recalls that of Quintilian, as proof of the care that was taken in its drafting, but having to take into account the multi-ethnic nature of the Empire, often reports, quoting them verbatim, both terms in sermo vulgaris and in the languages of the foederati: among other things, since it was also used by the imperial courts as evidence to resolve legal disputes on inheritance and the boundaries of landed properties, the Liber was quickly translated into the Germanic languages as well. As proof of this, we have fragments in Gothic and Alans.

This arduous undertaking, in reality, was a sort of holiday, according to the stories of Anicius Severus, for Flavius Constantius Felix, who also had to supervise the education of Theodosius and Valentinianus, given that Athaulf had realized that Galla Placidia had the tendency to spoil and be too permissive with the two puer. The fact that the two brothers were addicted to revelry, and then mended their ways, is probably a literary topos. The very story of the exchange, for a few days, between Theodosius and a poor boy from Ravenna is certainly an edifying tale. [7]

The two were probably nothing more than two restless teenagers: Theodosius probably already showed his qualities, his modesty, without eccentricity, except for his passion for hunting, inherited from his father, his knowledge of delegating and valorising his collaborators, his his administrative and military capabilities, his religious tolerance, and his defects, his closed, taciturn, harsh character, prone to outbursts of anger and sharp tongue. Valentinianus will have been the drudge, lover of erudition, obsessed, like Honorius, with micromanagement, lover of art and music and convinced, despite the opinion of the rest of the world, that he was a great poet!

[1] Census of Romans and federates

[2] Binding decision of the emperor

[3] Censuses specific to individual provinces, which like OTL, become the norm from the time of Diocletian onwards

[4] Which also happens OTL

[5] Totally ITL

[6] ITL the survival of these works is less coincidental

[7] The references to a certain novel are purely coincidental...

Beyond the events of Britain, the interests of Galla Placidia, in 428, were concentrated on a much more important and controversial issue, resuming an old idea of Honorius, that is, carrying out a census populi Romani atque Foederati, [1] which had become increasingly necessary due to social, demographic and economic changes that had occurred in the Empire in recent decades. The objective of the new census was to precisely quantify the imperial properties, about which Ravenna had somewhat confused ideas, the Roman properties and subjects, subject to taxation and military enlistment, and to understand how many laeti and foederati were actually established in the Empire, even due to the tendency of their comes, to minimize their economic and military commitments

According to Anicius Severus, Galla Placidia proposed this census to the Regency Council after the Christmas mass of 427; the main supporter of the proposal was for obvious reasons Questor thesauroum Flavius Iunius Quartus Palladius. However, the work on its organization proceeded quite slowly, as well as due to the opposition of the Roman senators, who feared that the objective of the census was to make their traditional tax avoidance practices more difficult, also due to a series of bureaucratic problems assignment of the task.

In fact, if Galla Placidia's objective was to assign the task to Palladius, given the needs of imperial finances, Flavius Constantius Felix, based on precedents, insisted on saying that it was the task of the Magister Officiorum to organize the census: in the end, to cut the head to the bull, a joint commission was organized, with representatives of both committees... Commission in which the representatives of Flavius Castinus also participated, both for the question of enlistments and because, knowing the landowners, someone could have reacted badly to the checks requested by the Ravenna administration.

After many and many discussions, in May 428, according to the majority of scholars, there is a minority that tends to move the date to August, shortly before the transfer of the imperial court for the summer holidays to Aquileia, an appropriate constitutio Principis [2] in which:

- A copy of the censua provincialia [3] was ordered to be sent to Ravenna, with partial data on the population of the individual provinces [4]

- The imperial commission would have collected and summarized these documents in the Liber Censuaria

- The officials of the imperial bureaucracy, with a series of inspections in the provinces, would have verified and updated the contents of the Liber Censuaria [5]

- The copies of the Liber Censuaria would be preserved in Ravenna, in Rome, in Mediolanum

- The procedure would be replicated every 25 years, once every generation.

The first fact that immediately caught the scholars' eyes is how the distribution of the localities is similar to that of the Tabula Peutingeriana; therefore, it is probable that the initial nucleus of this document was a sort of annex to the Liber, to allow imperial officials to identify the locations to inspect; only later, perhaps at the beginning of the 6th century, was it expanded and transformed into an autonomous document, becoming a representation of the road and commercial connections of the world known to the Romans at the time. The chapters are also structured according to the practical indications contained in the Corpus Agrimensorum Romanorum; therefore the hypothesis was also put forward that this collection of technical treatises was somehow connected to the census verification operation. [6]

Chapters that are divided into three distinct sections: the first dedicated to the imperial property, the second to the properties of the cives, the third to that of the foederati. For pagus and large estates, the extent of arable land is evaluated with the number of ploughs, each with eight oxen, available to work it, plus any others available; then the meadows, olive groves, vineyards, orchards, woods, pastures, fish ponds, water mills, salt pans and other sources of collateral income are listed; the colonists, slaves and associated wage laborers are enumerated in their different categories; finally, the annual income of the entire property is expressed approximately. For cities, for each building the rooms, the inhabitants, the connected economic activities and the associated income are enumerated.

The text, written in a literary Latin that recalls that of Quintilian, as proof of the care that was taken in its drafting, but having to take into account the multi-ethnic nature of the Empire, often reports, quoting them verbatim, both terms in sermo vulgaris and in the languages of the foederati: among other things, since it was also used by the imperial courts as evidence to resolve legal disputes on inheritance and the boundaries of landed properties, the Liber was quickly translated into the Germanic languages as well. As proof of this, we have fragments in Gothic and Alans.

This arduous undertaking, in reality, was a sort of holiday, according to the stories of Anicius Severus, for Flavius Constantius Felix, who also had to supervise the education of Theodosius and Valentinianus, given that Athaulf had realized that Galla Placidia had the tendency to spoil and be too permissive with the two puer. The fact that the two brothers were addicted to revelry, and then mended their ways, is probably a literary topos. The very story of the exchange, for a few days, between Theodosius and a poor boy from Ravenna is certainly an edifying tale. [7]

The two were probably nothing more than two restless teenagers: Theodosius probably already showed his qualities, his modesty, without eccentricity, except for his passion for hunting, inherited from his father, his knowledge of delegating and valorising his collaborators, his his administrative and military capabilities, his religious tolerance, and his defects, his closed, taciturn, harsh character, prone to outbursts of anger and sharp tongue. Valentinianus will have been the drudge, lover of erudition, obsessed, like Honorius, with micromanagement, lover of art and music and convinced, despite the opinion of the rest of the world, that he was a great poet!

[1] Census of Romans and federates

[2] Binding decision of the emperor

[3] Censuses specific to individual provinces, which like OTL, become the norm from the time of Diocletian onwards

[4] Which also happens OTL

[5] Totally ITL

[6] ITL the survival of these works is less coincidental

[7] The references to a certain novel are purely coincidental...

Oh, the dreary work of bureaucrats. If only it weren't so vital for the running of the state! Well, apparently Flavius Felix sees it differently, but I never had the pleasure of educating two young boys of higher status than myself.

Looks like we aren't so far off from Theodosius taking power, at least nominally. We'll see how that goes!

Looks like we aren't so far off from Theodosius taking power, at least nominally. We'll see how that goes!

Last edited:

41 A look at Constantinople

41 A look at Constantinople

It is interesting to note how the two branches of the Theodosian dynasty, East and West, were applying a totally opposite approach in managing the part of the Empire that had fallen to their lot. While in Ravenna, first reluctantly, then with growing awareness, the ethnic and religious plurality of the Empire had been acknowledged and in some way they were trying, with many contradictions, to transform it from a problem to an opportunity, in Constantinople, however, with the idea of a culturally homogeneous state was pursued with equal energy, heir to both the Greek and Latin traditions, as well as religiously, in which the Emperor's opinions on Christianity had to be imposed, even by force, on all citizens. .

This principle also had repercussions in politics towards the Germanic and Danubian populations: if Ravenna, which had forcibly suffered their admiration, tried to integrate them as foederati, using both the stick and the carrot, in Constantinople the principle of inviolability was in force any cost of borders. Under no circumstances were barbarian populations to be settled within the Pars Orientis. For no reason and at any cost and this means the fact that if military resources did not allow us to face the Huns or other turbulent neighbors, it would certainly be more appropriate to become tributaries of them, organize an annual tribute, make them a donation, with the assurance of their removal from the lands of the empire: following the reasoning according to which one prefers to take without fighting than to take by fighting. This different vision of politics was obviously combined with contingent causes, from the terrible character of Honorius to the question of Hillyricus, on which it was not possible to find a dignified compromise between the two parts of the Empire. All issues of which people in Constantinople were more or less aware, but which were put into the background, due to two immediate issues, the first political, the second economic.

Ravenna, unlike Constantinople, had managed to obtain a collaborative relationship with the Huns: therefore, the help and mediation of Galla Placidia was necessary for the Balkan border to remain peaceful; the other was the continued resumption of trade and commercial traffic between the two parts of the Empire, due both to the calming of the situation in the Pars Occidentis and to the resourcefulness of the Suebi and the Roman senatorial class. [1]

In recent decades, with the mass of discoveries of artefacts, especially ceramics, we have an increasingly clear idea of these exchanges: paradoxically, one of the main vectors of such economic contacts is beginning to be pilgrimages, with notable masses of Christians, both Niceans, both Arians, which includes high prelates, monks, but also simple believers, who move between the three poles of what can be considered the ancestor of our religious tourism, namely Jerusalem, Rome and Constantinople. The penitents and pilgrims effectively opened the path to commercial caravans, as evidenced by the analysis of the routes of both types of travellers, reconstructed thanks to the comparison between literary sources and archaeological sources. [2]

A consequence of these pilgrimages, for example, is the spread of amber jewels in the East, spread in the West thanks to the maritime trade of the Suebi and the land trade of the subjects of the Huns, via a trade route that linked the Baltic coasts with the Pannonian settlements and which it ended in Aquileia; pilgrims who visited Constantinople or Jerusalem left amber jewels as votive offerings, which contributed to making them fashionable in the Pars Orientis. [3]

From what we have managed to reconstruct, the first fulcrum of these trades was Mediolanum on which three different directions converged: the first came from Genoa, which was beginning its expansion at the time, on which the maritime routes of the Sueni coming from Spain and Suburban Italy. [4] The second commercial route came from Gaul, passing through Augusta Pretoria [5] and Augusta Taurinorum. [6] The third, coming from the Rhenish provinces and Germania Magna, was that of Spluga, due to the easy practicability of the access valleys and as it allowed crossing the Alps via a single crossing point; it connected Comum [7]with Chiavenna via a route along the right bank of Lake Como, today called "strada Regina"; alternatively it was possible to complete this stretch by sailing on the Lario. The Mediolanum-Comum-Cuneus Aureus [8]-Curia-Brigantium [9]axis, which established itself for its notable strategic value, is mentioned in the Tabula Peutingeriana.

In the vast territory in which Mediolanum served as the hub of traffic, the land communications network was integrated by river routes, made up of waterways of almost constant flow, such as to allow navigation in any season of the year. Over time, the physiognomy of the landscape has undergone numerous alterations, making it difficult to reconstruct internal navigation routes, but in ancient times the Po was navigable up to Augusta Taurinorum. The most popular routes can be deduced from itinerary and literary sources: a navigation line on the Lario; a service on the Po; intra-lagoon navigation in the Po delta area; a route to Padum [10] from Ravenna to Hostilia [11] (along the Augusta trench and the Padum). Along the Po river the waterway connection was maintained by the cursus publicus, at least for the Ticinum [12]-Ravenna stretch, the natural outlet for navigation in the Po Valley. The service took place in several stages, touching important river ports, such as Cremona, Brixellum, [13] Hostilia. Many tributaries of the Po were also navigable: from Ticinum you went up the Verbanus; [14]the confluence of the Adda allowed the penetration towards Laus Pompeia, [15]the lakes of Olginate, Lecco up to the Lacus Larius [16]and, through the Mera, up to Clavenna and the passes for the Retia, the Vindelicia, the Germanie, while the confluence of the Oglio it allowed you to reach the markets of Bergomum [17] and Brixia. [18] Via Postumia and Via Gallica were reachable via the Mincio, then entering Lacus Benacus. [19] Within the coastline from Ravenna to Aquileia, navigable channels, river branches and lagoon spaces guaranteed the continuity of a route, allowing regional traffic to integrate into transalpine trade. [20]

From Aquileia and Ravenna, then, a route started which, crossing the Adriatic, headed towards the Peloponnese and then towards Crete, where it divided into two branches, one directed towards Egypt, the other towards Cyprus, from where in turn it bifurcated towards Syria and Palestine and towards Constantinople; maritime trade which from the wrecks dating back to that era, such as that of Marzameni, used much larger ships than in the 3rd century, due to the partial replacement of the amphorae with wooden barrels, due to the progressive differentiation of the transported goods.

As proof of the importance given to the court of Ravenna for this trade, is the appointment of a Comes Commerciorum per Orientem et Aegyptum [21] in September 428, which from the testimony of Anicius Severus, is Flavius Veremondus, a romanized Suebus, who had done career taking care of the affairs of the powerful Anicii family. Now in Constantinople they were aware of the economic importance of such trade: therefore, all the policies of Theodosius II, despite ideological differences, were aimed at maintaining good relations with Galla Placidia, which allowed him to have a free hand towards Armenia , where, however, in 428, it received a serious diplomatic defeat by the Sassanid Empire.

With the Peace of Acilisene in 387, Armenia was in fact divided into two parts: Lesser Armenia was definitively incorporated into the Pars Orientis, while Persarmenia became a vassal state of the Sassanid empire. From 427 onwards, Theodosius II began to send subsidies to the Armenian king Artaxias IV to rebel against the Persians, also promising military intervention by the Romans, so that Persarmenia would become a vassal of Constantinople. Also supporting this adventurous policy was the Catholikos of Armenia Sahak, who was fearful that the Persian presence would lead to the replacement of Christianity with Zoastrianism. To gain his support, Theodosius promised the Catholikos that Armenian would replace Greek and Syriac as the ecclesiastical language. [22]

Now, if in place of Theodosius II there had been an Honorius or a Galla Placidia, or if Artaxias IV had not been a complete idiot, this intrigue could have had a minimal chance of success: but the Armenian nobles, the nakharar, fearful of seeing their properties reduced to a battlefield between Romans and Persians and suspicious that Artaxias IV, who had timidly initiated a policy of centralization, could attack their privileges, asked for help from the Persian Shah Bahram V, who with a coup de main , dethroned Artaxias IV and replaced the Catholicos Sahak with the Syrian Bar Kiso, more loyal to the Sasanian cause.

Obviously, Bahram V had no intention of facing a revolt of the nakharar, which would certainly have been unleashed if he had tried to touch their privileges, nor of unleashing, given the recent defeats, a war against the Roman Empire, so, the annexation changed very little of the previous state. Instead of a king, Persarmenia was governed by a Marzban, appointed by the assembly of nakharar; despite being a royal representative, invested with full administrative and judicial powers, he could not interfere with the privileges of the nakharar. To guarantee the autonomy of Persarmenia, both the Hazarepet, who was the right arm of the Marzaban, being responsible for public order, public works, tax collection and budget management, and the Sparapet, the head of the garrison Sasanian, had to be chosen among the nakharar, who in addition to not paying taxes, could maintain their own private army. Furthermore, all state officials, including tax collectors, had to be Armenian, and the courts and schools were run by local clergy. Furthermore, Bahram V, with much greater wisdom than his successors, undertook to respect the Christian religion and not impose Zoastrianism on the Armenians. Finally, to reassure Theodosius II, the nakharar assembly appointed Marzban Veh Mihr Shapur, who had previously had good relations with Constantinople. [23]

The problem is that both Bahram V and the nakharar had underestimated the terrible character of Theodosius' descendants... Therefore, Theodosius II in November 428 sent an embassy to both the Hepthalites and the Kidarites, to ask for an anti-Sasanian alliance . [24] All this diplomatic activism, which belied the traditional indolence of the Roman emperor, however made him miss what was happening under his nose in Constantinople. On 10 August 428 Nestorius was appointed Patriarch of Constantinople: born in Germanicia in the Roman province of Syria probably in 381, he entered the convent of Euprepios, near Antioch, as a child, and received his theological training from the Antiochian school, of which Theodore was head of Mopsuestia. The school of Antioch, in full reaction to Apollinarianism, realistic and anti-allegorical in its exegesis, was entirely attentive to the human reality of the life of Christ, which the mystical disposition of the rival school of Alexandria tended to submerge in the divine nature, something that in the future will bring him to loggerheads with Cyril of Alexandria.

If the new patriarch shared the position of the church of Rome on the dispute between Augustine and Pelagius, seeking a theological compromise between the two positions, he was instead very rigid towards the Arians, considered enemies of Christianity, asking Theodosius II for the integral application of the imperial laws against heretics, while Coelestinus, for political reasons, applied the "live and let live" policy towards them. Furthermore, what worsened his fame among the plebs and the clergy of Constantinople was his request, fortunately ignored by the Court, because it would certainly have triggered a revolt, to abolish the races in the Hippodrome, considered immoral, and for having initiated a reform of the clergy in the ascetic sense... In short, Nestorius was showing great skill in making enemies and looking for trouble... [25]

[1] Obviously butterflies, even economic ones, reach the East!

[2] ITL the phenomenon is anticipated by a couple of centuries

[3] Another change from OTL, which strengthens the trade routes of the time and the Romanization of the Baltic

[4] Here too things are anticipated by several centuries...

[5] Aosta

[6] Turin

[7] Como

[8] Spluga Pass

[9] Bregenz

[10] Po river

[11] Ostiglia, near Mantua

[12] Pavia

[13] Brescello, yes the village of Guareschi's novels with Peppone and Don Camillo

[14] Lake Maggiore

[15] Lodi Vecchio

[16] Lake Como

[17] Bergamo

[18] Brescia

[19] Lake Garda

[20] The text is a summary of a chapter of Marco Alessi's book, "The Po Valley in Late Antiquity"

[21] Count responsible for trade with the East and Egypt, invented position ITL

[22] Compared to OTL, having fewer problems with the West and the Huns, Theodosius II is more active against the Sasanians

[23] Increased Roman pressure makes Armenia the OTL equivalent of our Polish-Lithuanian confederation, causing a riot of chaos and entropy

[24] Butterflies and problems coming for the Sasanians!

[25] You thought I'd forgotten about him!

It is interesting to note how the two branches of the Theodosian dynasty, East and West, were applying a totally opposite approach in managing the part of the Empire that had fallen to their lot. While in Ravenna, first reluctantly, then with growing awareness, the ethnic and religious plurality of the Empire had been acknowledged and in some way they were trying, with many contradictions, to transform it from a problem to an opportunity, in Constantinople, however, with the idea of a culturally homogeneous state was pursued with equal energy, heir to both the Greek and Latin traditions, as well as religiously, in which the Emperor's opinions on Christianity had to be imposed, even by force, on all citizens. .

This principle also had repercussions in politics towards the Germanic and Danubian populations: if Ravenna, which had forcibly suffered their admiration, tried to integrate them as foederati, using both the stick and the carrot, in Constantinople the principle of inviolability was in force any cost of borders. Under no circumstances were barbarian populations to be settled within the Pars Orientis. For no reason and at any cost and this means the fact that if military resources did not allow us to face the Huns or other turbulent neighbors, it would certainly be more appropriate to become tributaries of them, organize an annual tribute, make them a donation, with the assurance of their removal from the lands of the empire: following the reasoning according to which one prefers to take without fighting than to take by fighting. This different vision of politics was obviously combined with contingent causes, from the terrible character of Honorius to the question of Hillyricus, on which it was not possible to find a dignified compromise between the two parts of the Empire. All issues of which people in Constantinople were more or less aware, but which were put into the background, due to two immediate issues, the first political, the second economic.

Ravenna, unlike Constantinople, had managed to obtain a collaborative relationship with the Huns: therefore, the help and mediation of Galla Placidia was necessary for the Balkan border to remain peaceful; the other was the continued resumption of trade and commercial traffic between the two parts of the Empire, due both to the calming of the situation in the Pars Occidentis and to the resourcefulness of the Suebi and the Roman senatorial class. [1]

In recent decades, with the mass of discoveries of artefacts, especially ceramics, we have an increasingly clear idea of these exchanges: paradoxically, one of the main vectors of such economic contacts is beginning to be pilgrimages, with notable masses of Christians, both Niceans, both Arians, which includes high prelates, monks, but also simple believers, who move between the three poles of what can be considered the ancestor of our religious tourism, namely Jerusalem, Rome and Constantinople. The penitents and pilgrims effectively opened the path to commercial caravans, as evidenced by the analysis of the routes of both types of travellers, reconstructed thanks to the comparison between literary sources and archaeological sources. [2]

A consequence of these pilgrimages, for example, is the spread of amber jewels in the East, spread in the West thanks to the maritime trade of the Suebi and the land trade of the subjects of the Huns, via a trade route that linked the Baltic coasts with the Pannonian settlements and which it ended in Aquileia; pilgrims who visited Constantinople or Jerusalem left amber jewels as votive offerings, which contributed to making them fashionable in the Pars Orientis. [3]

From what we have managed to reconstruct, the first fulcrum of these trades was Mediolanum on which three different directions converged: the first came from Genoa, which was beginning its expansion at the time, on which the maritime routes of the Sueni coming from Spain and Suburban Italy. [4] The second commercial route came from Gaul, passing through Augusta Pretoria [5] and Augusta Taurinorum. [6] The third, coming from the Rhenish provinces and Germania Magna, was that of Spluga, due to the easy practicability of the access valleys and as it allowed crossing the Alps via a single crossing point; it connected Comum [7]with Chiavenna via a route along the right bank of Lake Como, today called "strada Regina"; alternatively it was possible to complete this stretch by sailing on the Lario. The Mediolanum-Comum-Cuneus Aureus [8]-Curia-Brigantium [9]axis, which established itself for its notable strategic value, is mentioned in the Tabula Peutingeriana.

In the vast territory in which Mediolanum served as the hub of traffic, the land communications network was integrated by river routes, made up of waterways of almost constant flow, such as to allow navigation in any season of the year. Over time, the physiognomy of the landscape has undergone numerous alterations, making it difficult to reconstruct internal navigation routes, but in ancient times the Po was navigable up to Augusta Taurinorum. The most popular routes can be deduced from itinerary and literary sources: a navigation line on the Lario; a service on the Po; intra-lagoon navigation in the Po delta area; a route to Padum [10] from Ravenna to Hostilia [11] (along the Augusta trench and the Padum). Along the Po river the waterway connection was maintained by the cursus publicus, at least for the Ticinum [12]-Ravenna stretch, the natural outlet for navigation in the Po Valley. The service took place in several stages, touching important river ports, such as Cremona, Brixellum, [13] Hostilia. Many tributaries of the Po were also navigable: from Ticinum you went up the Verbanus; [14]the confluence of the Adda allowed the penetration towards Laus Pompeia, [15]the lakes of Olginate, Lecco up to the Lacus Larius [16]and, through the Mera, up to Clavenna and the passes for the Retia, the Vindelicia, the Germanie, while the confluence of the Oglio it allowed you to reach the markets of Bergomum [17] and Brixia. [18] Via Postumia and Via Gallica were reachable via the Mincio, then entering Lacus Benacus. [19] Within the coastline from Ravenna to Aquileia, navigable channels, river branches and lagoon spaces guaranteed the continuity of a route, allowing regional traffic to integrate into transalpine trade. [20]

From Aquileia and Ravenna, then, a route started which, crossing the Adriatic, headed towards the Peloponnese and then towards Crete, where it divided into two branches, one directed towards Egypt, the other towards Cyprus, from where in turn it bifurcated towards Syria and Palestine and towards Constantinople; maritime trade which from the wrecks dating back to that era, such as that of Marzameni, used much larger ships than in the 3rd century, due to the partial replacement of the amphorae with wooden barrels, due to the progressive differentiation of the transported goods.

As proof of the importance given to the court of Ravenna for this trade, is the appointment of a Comes Commerciorum per Orientem et Aegyptum [21] in September 428, which from the testimony of Anicius Severus, is Flavius Veremondus, a romanized Suebus, who had done career taking care of the affairs of the powerful Anicii family. Now in Constantinople they were aware of the economic importance of such trade: therefore, all the policies of Theodosius II, despite ideological differences, were aimed at maintaining good relations with Galla Placidia, which allowed him to have a free hand towards Armenia , where, however, in 428, it received a serious diplomatic defeat by the Sassanid Empire.

With the Peace of Acilisene in 387, Armenia was in fact divided into two parts: Lesser Armenia was definitively incorporated into the Pars Orientis, while Persarmenia became a vassal state of the Sassanid empire. From 427 onwards, Theodosius II began to send subsidies to the Armenian king Artaxias IV to rebel against the Persians, also promising military intervention by the Romans, so that Persarmenia would become a vassal of Constantinople. Also supporting this adventurous policy was the Catholikos of Armenia Sahak, who was fearful that the Persian presence would lead to the replacement of Christianity with Zoastrianism. To gain his support, Theodosius promised the Catholikos that Armenian would replace Greek and Syriac as the ecclesiastical language. [22]

Now, if in place of Theodosius II there had been an Honorius or a Galla Placidia, or if Artaxias IV had not been a complete idiot, this intrigue could have had a minimal chance of success: but the Armenian nobles, the nakharar, fearful of seeing their properties reduced to a battlefield between Romans and Persians and suspicious that Artaxias IV, who had timidly initiated a policy of centralization, could attack their privileges, asked for help from the Persian Shah Bahram V, who with a coup de main , dethroned Artaxias IV and replaced the Catholicos Sahak with the Syrian Bar Kiso, more loyal to the Sasanian cause.

Obviously, Bahram V had no intention of facing a revolt of the nakharar, which would certainly have been unleashed if he had tried to touch their privileges, nor of unleashing, given the recent defeats, a war against the Roman Empire, so, the annexation changed very little of the previous state. Instead of a king, Persarmenia was governed by a Marzban, appointed by the assembly of nakharar; despite being a royal representative, invested with full administrative and judicial powers, he could not interfere with the privileges of the nakharar. To guarantee the autonomy of Persarmenia, both the Hazarepet, who was the right arm of the Marzaban, being responsible for public order, public works, tax collection and budget management, and the Sparapet, the head of the garrison Sasanian, had to be chosen among the nakharar, who in addition to not paying taxes, could maintain their own private army. Furthermore, all state officials, including tax collectors, had to be Armenian, and the courts and schools were run by local clergy. Furthermore, Bahram V, with much greater wisdom than his successors, undertook to respect the Christian religion and not impose Zoastrianism on the Armenians. Finally, to reassure Theodosius II, the nakharar assembly appointed Marzban Veh Mihr Shapur, who had previously had good relations with Constantinople. [23]

The problem is that both Bahram V and the nakharar had underestimated the terrible character of Theodosius' descendants... Therefore, Theodosius II in November 428 sent an embassy to both the Hepthalites and the Kidarites, to ask for an anti-Sasanian alliance . [24] All this diplomatic activism, which belied the traditional indolence of the Roman emperor, however made him miss what was happening under his nose in Constantinople. On 10 August 428 Nestorius was appointed Patriarch of Constantinople: born in Germanicia in the Roman province of Syria probably in 381, he entered the convent of Euprepios, near Antioch, as a child, and received his theological training from the Antiochian school, of which Theodore was head of Mopsuestia. The school of Antioch, in full reaction to Apollinarianism, realistic and anti-allegorical in its exegesis, was entirely attentive to the human reality of the life of Christ, which the mystical disposition of the rival school of Alexandria tended to submerge in the divine nature, something that in the future will bring him to loggerheads with Cyril of Alexandria.

If the new patriarch shared the position of the church of Rome on the dispute between Augustine and Pelagius, seeking a theological compromise between the two positions, he was instead very rigid towards the Arians, considered enemies of Christianity, asking Theodosius II for the integral application of the imperial laws against heretics, while Coelestinus, for political reasons, applied the "live and let live" policy towards them. Furthermore, what worsened his fame among the plebs and the clergy of Constantinople was his request, fortunately ignored by the Court, because it would certainly have triggered a revolt, to abolish the races in the Hippodrome, considered immoral, and for having initiated a reform of the clergy in the ascetic sense... In short, Nestorius was showing great skill in making enemies and looking for trouble... [25]

[1] Obviously butterflies, even economic ones, reach the East!

[2] ITL the phenomenon is anticipated by a couple of centuries

[3] Another change from OTL, which strengthens the trade routes of the time and the Romanization of the Baltic

[4] Here too things are anticipated by several centuries...

[5] Aosta

[6] Turin

[7] Como

[8] Spluga Pass

[9] Bregenz

[10] Po river

[11] Ostiglia, near Mantua

[12] Pavia

[13] Brescello, yes the village of Guareschi's novels with Peppone and Don Camillo

[14] Lake Maggiore

[15] Lodi Vecchio

[16] Lake Como

[17] Bergamo

[18] Brescia

[19] Lake Garda

[20] The text is a summary of a chapter of Marco Alessi's book, "The Po Valley in Late Antiquity"

[21] Count responsible for trade with the East and Egypt, invented position ITL

[22] Compared to OTL, having fewer problems with the West and the Huns, Theodosius II is more active against the Sasanians

[23] Increased Roman pressure makes Armenia the OTL equivalent of our Polish-Lithuanian confederation, causing a riot of chaos and entropy

[24] Butterflies and problems coming for the Sasanians!

[25] You thought I'd forgotten about him!

John Fredrick Parker

Donor

Excited for the Nestorius post!

A thought I had before on this:

<snip>

First of all, he continues to be bishop of the diocese of Aeclanum, he will not be deposed (among other things, Aeclanum will never be abandoned, as a city) and he will continue to dedicate himself to theology: if his controversy with Augustine will be less harsh, however, unlike OTL, he will argue heatedly with Nestorius, accusing him of being crypto-Aryan. Upon his death, he will be venerated as a saint by the Nicean Church

It will be very interesting to watch how the political and religious culture of the two Roman states will diverge due to happenstance and political realities. The West couldn't copy the East even if they wanted to, after having been badly rocked at the start of the century. Even if they are recovering now.It is interesting to note how the two branches of the Theodosian dynasty, East and West, were applying a totally opposite approach in managing the part of the Empire that had fallen to their lot. While in Ravenna, first reluctantly, then with growing awareness, the ethnic and religious plurality of the Empire had been acknowledged and in some way they were trying, with many contradictions, to transform it from a problem to an opportunity, in Constantinople, however, with the idea of a culturally homogeneous state was pursued with equal energy, heir to both the Greek and Latin traditions, as well as religiously, in which the Emperor's opinions on Christianity had to be imposed, even by force, on all citizens. .

This divergent evolution might provide for a really spicy narrative, should a temporary reunification of the Empire come about in the future.

Ah yes, obviously Constantinople wouldn't see the irony in wanting to be more Roman and unsullied by Barbarians than the West... Anyway it was expected a new confrontation with Persia soon or later would come.

I am glad that Milan is blooming culturally and economically in the meanwhile! It just needs to emerge religiously as well and likely soon would...

I am glad that Milan is blooming culturally and economically in the meanwhile! It just needs to emerge religiously as well and likely soon would...

42 The Wandering Jew

42 The Wandering Jew