*mean girls voice* Quit trying to make the Union of the British Isles happen!Thank God, the union of the british isles will happen under that better dynasty?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Grand Duchy of the West - A Valois-Burgundian TL

- Thread starter BlueFlowwer

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 58 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 47 - England from 1523 to 1526 Chapter 48 - Brabant, France and England from 1525 to 1527 Chapter 49 - Spain and the Holy Roman Empire 1523 to 1525 Chapter 50 - Spain and the Holy Roman Empire from 1525 to 1526 Chapter 51 - Brabant, France and the Holy Roman Empire in 1527 Chapter 52 - Spain from 1527 to 1528 Chapter 53 – England in September of 1528 Chapter 54 - Brabant and France in 1528🤣🤣🤣🤣*mean girls voice* Quit trying to make the Union of the British Isles happen!

*mean girls voice* Quit trying to make the Union of the British Isles happen!

But you have to admit, that would be so fetch!*mean girls voice* Quit trying to make the Union of the British Isles happen!

We will see what happens. Maybe Scotland will rule the world.But you have to admit, that would be so fetch!

Ugh, let's hope not.We will see what happens. Maybe Scotland will rule the world.

That would be interesting for future alliances, the British Isles remain disunited but in contrast we have the birth of the Kingdom of Spain almost a century and a half earlier under Juan.

The whole Castile and Aragon being ruled by a native spanish king is definitely gonna speed certain things up.

That's for sure, let's hope the House of Trastamara can get their affairs in order as well before the gig is up for them.The whole Castile and Aragon being ruled by a native spanish king is definitely gonna speed certain things up.

Well, it's not gonna be a perfect utopia every year, but on the whole things are gonna become somewhat better.That's for sure, let's hope the House of Trastamara can get their affairs in order as well before the gig is up for them.

Cool, Juan will definitely live up to his parents expectations.Well, it's not gonna be a perfect utopia every year, but on the whole things are gonna become somewhat better.

And Portugal will do well with Alfonso and Isabella at the helm.Yep!

Yep, the only legitimate son of the Perfect Prince and eldest daughter of the Catholic monarchs sure will be a power couple in Portugal and ensure the continuation of the Aviz Dynasty.And Portugal will do well with Alfonso and Isabella at the helm.

I've started with their chapter, but I'm a bit busy with new job right now.Yep, the only legitimate son of the Perfect Prince and eldest daughter of the Catholic monarchs sure will be a power couple in Portugal and ensure the continuation of the Aviz Dynasty.

Again, wish you the best of luck with the job.I've started with their chapter, but I'm a bit busy with new job right now.

😊😊😊Again, wish you the best of luck with the job.

Chapter 15 - Brabant from 1490 to 1500

Chapter 15 - Brabant from 1490 to 1500

Anne of Burgundy would leave for her imperial bridegroom in 1493 as Archduke Frederick turned fourteen years old. Her entourage left Brussels in late summer to travel to Aachen along with her brother, nephew, and sister-in-law. Little Philippe, Count of Namur (as Charolais was not available anymore) travelled with his family. His parents were determined that his education would include diplomatic matters such as this. Both families would meet up in Aachen with Maximilian and Anne would be received by her new family. Also more importantly, Maximilian was to be elected Holy Roman Emperor in the cathedral of Charlemagne now that he was the ruler of the empire. His successful election in Hungary had given him higher status, even if the first years had been marked with struggles of all kinds.

Philip took one important item with him to Aachen. A coronet owned by his mother Margaret; it had been given by Charles the Bold at the wedding. The coronet itself trimmed with pearls, precious stones and enamelled white roses. The presentation of the dowager’s crown to one of the oldest cathedrals in Europe, constructed by Charlemagne, by the Duke of Brabant carried strong implications. Aachen was the traditional crowning place of the Holy Roman Emperors and the old emperor, The ascension of Maximilian became imminent, as the king of the romans was the title of the imperial successor.

Crown of Margaret of York, Aachen Cathedral

The leading man for the Hapsburg meeting was Eitel Friedrich II, Count of Hohenzollern, one of Maximilian’s most trusted men. He accompanied Maximilian to Aachen, overseeing his entourage. Philip and his family arrived in Aachen in the first week of September, when the trees had just started to turn golden. For Philippa, the old city of Aachen was a beautiful sight, and Philippe was as impressed as a child could be. The Duke and Duchess were greeted at Aachen by Johann Beissel, mayor of the city, who had offered the Aachen Town Hall as residence during their stay. Philip got the entourage and the packings settled in, while Philippa and her ladies rested, afterwards they spent the rest of the evening discussing matters of state with Johann.

The Hapsburg delegation arrived seven days later. The duke and duchess of Brabant greeted him upon his arrival, and Frederick and Anne were introduced later in the evening. Several days of banquets and festivities followed, as Philip gave gift for Frederick. Maximilian in turn gave Philip a bejewelled sword and a richly harnessed stallion in return. More practical matters were also as hand. The renewal of the Burgundian-Hapsburg alliance and matters of trade between realms were discussed. But the core reason for the meeting had been finished and after the two weeks had passed, several days was spent hunting and jousting, to the delight of the people of Aachen. In the last days of September 1493, the ducal couple left Aachen to return to Namur in the low countries.

The Golden Age of Flanders is believed to have started around 1480, and Philip’s reign marked the first part of it. In 1494 Philip had ruled for almost a decade on his own and at the age of twenty-five he was a father of four living children and one unborn. He had become a promising ruler, well acquainted with his people. Philip was an excellent horseman, a skilled linguist and had become an excellent orator (taking after his late father), as well as a good chess player. His education had been managed by the very best scholars in the duchy, both in humanist subjects and science (Philip was a hobby astronomer) and theologian matters. Like his mother he showed interest in the humanist movement and her love for books. He inherited his mother’s height and his father’s stockiness, standing solidly at 6,2 feet. Brown haired and green eyed, with a soft mouth and large ears, Philip made for a handsome man, catching the eyes of the court ladies rather quick. In temper Philip took after his mother: sober manners, determination in his action, an openness to his subjects. From both parents he inherited a restless energy and a sober attire unless there was a grand occasion. Blue, black, or dark clothing was a staple of his wardrobe, warm velvets, or summer silks. Philip favoured efficiency and his household had to move with him, slackers did not last long in his company. His circle of friends consisted of young knights in training, the sons of ducal governors and young noblemen. Many of these men would remain loyal to him for his entire life. From his father he inherited a fierce temper, but it did not appear often. He was also less rash than his predecessor and a better tactician.

The state of the Low Countries in 1493 was one of peace and prosperity. Scars from the years from 1477-81 had healed and Brabant had peace with their neighbours. Philip and Philippa spent a lot of time with agricultural projects, as the loss of the Duchy of Burgundy had left the fruitful fields the areas lost. The damaged fields in Luxembourg and the planes of Brabant had been restored years ago, with resources granted to plant new fields and orchards around the duchy. The farmers in the areas were given a ducal exempt from taxation for a whole year, in return for establishing the new fields. Manufacturers increased production in agricultural equipment after 1480 and the products were distributed to the most needed areas. Philip made several visits to the County of Burgundy, where wine orchards flourished, cheese makers thrived and cattle grazed in the fields. Grainfields popped up all over the duchy from Dóle to Breda for the past fifteen years, becoming a reliable food source for many.

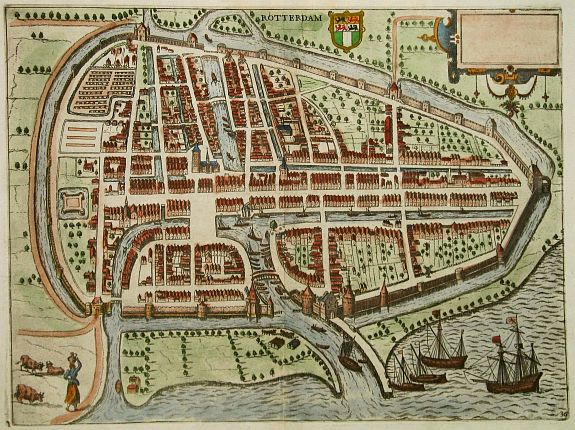

Flanders, Brabant, Hainault, Artois, Picardy and Holland prospered in 1495. The shipyards bustled with activity. Maximilian had given Philip right to import lumber and stone free of custom duties from the German forests since 1486. The lumber also got sent to the shipyards in Holland and Zeeland. Rotterdam in south Holland would become one of the greatest ports in the Low Countries under Philip’s reign.

Rotterdam under the renaissance age

The surplus of lumber was used in rebuilding villages and equipment’s for better living. Amsterdam thrived with builders, rope makers and metalsmiths. The years of peacetime since 1487 had left the duchy with considerable wealth and the efficient government had a surplus of resources. The ducal debt from Charles the Bold had all been paid by 1490, without extra taxation. The cities bustled with productivity, the law officers kept the crime levels to a minimum, new buildings such as churches and farms popped up like mushrooms after rain. One sad note was the death of Jehan van Dadizele in 1498, the lieutenant general of Flanders had passed away. Jehan had been an important member of Philip’s councillors, particularly during times of trouble. Jehan had been interred in the Saint Nicholas Church in Ghent, with the expenses born by the duke. Philip had even ordered a marble effigy to honour him.

With his realm thriving Philip began to look towards the rest Europe’s royal houses to secure foreign allies for the future. In 1495 Philip and Philippa had five living children, nine-year-old Philippe, Count of Namur, Jean born in 1488, Margaretha in 1490, Arnold in 1491 and baby Katherine, born in the spring of 1495. Jean was already betrothed to Marie d’Albret but plans for Philippe’s and Margaretha’s marriages began after Katherine’s birth with strategy in mind. Two ducal delegations left from Bruges in the summer, to London and Copenhagen.

Philip himself was the son of an english mother and the old Anglo-Flemish alliance took priority again. At Christmas in 1495, an agreement was struck between Burgundy and England. Richard III’s and Beatrice of Portugal’s eldest daughter, Beatrice of England, would marry Philippe in 1503 when she turned sixteen. The match was heavily supported by dowager duchess Margaret of York, who had spent all her life since 1468 to maintain the relationship between her homeland and her marriage land. Beatrice had grown into a healthy and active eight-year-old girl. The princess had started her education, held by her mother and selected tutors.

Beatrice of England in 1510

With the arrangements for his heir in place, Philip turned his eye towards the north, to Denmark and King Hans. The relationship between the Dutch merchants and the Hanseatic League had led to the rivalries in the 15th century, with the formerly powerful league of merchants had encountered difficulties of different sorts. A new medium of exchange had been imported from Italy, the double-entry bookkeeping, to control finances. It had been invented in 1492 and Philip had ordered many of the large cities, such as Amsterdam, Antwerp, as well as the Flemish cities to learn it. The Hansa still used silver coins to exchange currency at this point, to their detriment. The building of shipyards in Holland and Zeeland had also been a part of Philip’s strategy to weaken the Hansa, as the league sold ships in every part of Europe. The alliance with the Holy Roman empire meant that the Dutch gained access to direct trade with several of the German princes, cutting out the Hansa as middlemen. The lower costs of trading with the ducal merchants also left the league weaker. Philip pushed hard for dominance against the Hansa with success. The naval wars ensured a monopoly for Polish and Baltic grains for Amsterdam and Antwerp in the 1490s. The match between Copenhagen and Brabant would be another link in Philip’s ambitions. Crown prince Christian was fourteen years old, his potential bride, Margaretha five.

Margaretha of Brabant in 1501

Philip also found a possible bridegroom for baby Katherine in 1496. Jean VI of Brittany had married Eleanor of Gloucester in 1494, and their first son, Richard (also named for Jean’s grandfather Richard, Count of Montfort, Vertus and Étampes) would be born in February. The Duchies of Brabant and Brittany had been allied since Jean’s birth as Charles the Bold had been named godfather before his death that year. Since Francis II of Brittany had broken off the engagement with Anne of Burgundy in 1486, Philip offered Katherine’s hand to baby Richard as a renewal of their alliance and offered to be godfather.

Katherine of Brabant in 1503

Only little Arnold was left without a betrothal in 1496, but as history would turn out his marriage would become every bit as grand as his siblings.

The ducal children were all thriving in 1496, the three youngest living at their grandmother’s court in Malines. The dowager spending most of her time in her palace as well as Binche, one of her dower cities, and Ter Elst, a countryside castle to get away from the dust of the cities. Philippe and Jean resided with the court and travelled with their parents around the duchy, until 1497 when they established their own households in Ghent and Rethel.

Duke Philip met a man in 1492, who would become a life-long friend. A poor scholar named Erasmus who had taken wows in the canonry of Stein in south Holland in 1488. Erasmus had been ordained to the catholic priesthood at the same time the duke was in the area, to issue charters to the shipyards in Rotterdam. Erasmus made the bold move to see the duke and try to gain patronage. After much persuasion, he succeeded in getting an audience in June in Amsterdam. Erasmus had a reputation as a man of letters already before his meeting and while Philip had not read any of his writing, he knew the man’s name.

Erasmus of Rotterdam who barged his way into the ducal household.

What the meeting between Erasmus and the duke consisted of is unknown, but the scholar’s skill in Latin, Greek and erudition seemed to have impressed Philip. Erasmus got a sum of 30 marks by Philip to purchase “necessaries such as writing tools and otherwise”. Erasmus also brough new clothing. A horse and four escorts were also provided by the duke, who intended to put Erasmus to use as a tutor for his eldest children, Philippe, and Jean, now six and four years old. It was high time for them to move past basic learning. Erasmus travelled to Malines, to the court of the dowager duchess Margaret.

Becoming the tutor to the heirs to Brabant was way beyond what Erasmus had hoped for and being given a home in the revered dowager’s palace bore enormous prestige. The duke had trusted him to educate his children. For Erasmus, this was an important win. Dowager Margaret welcomed Erasmus into her home with warmth, the two being very much alike. And the scholar who entered the canonry due to poverty in 1487 would find himself playing chess at evenings with the dowager duchess of Burgundy five years later.

For Margaret of York, dowager Duchess of Burgundy the years since 1486 had been mostly peaceful. The death of her niece Mary of York and firstborn grandson Charles had taken a hard toll on her, but she had recovered afterwards and Philippa of Guelders proved to be an exemplary daughter in law, lifting her spirit from grief. While her son had his hands busy with annihilating the Hanseatic League from the Dutch trading routes and undercutting them with offers, Margaret did not stay idle. Like many women of the times, she took full advantage of widowhood. After her regency was over, she enjoyed a considerable independence with financial security. She raised her grandchildren, stayed updated on politics, and oversaw the administration of her dower lands. In 1493 she had granted Philip her property at Le Quesnoy near the French border, a difficult strategic place for the older dowager to hold. Le Quesnoy lay near Mormail, a vast hunting forest. It suited the active duke and duchess much more than the dowager and the court would hold grand hunts and feasts for many decades. Philip repaired the old castle in the area, using it as a hunting lodge and summer estate, refurbished with Flemish decorations and Castilian carpets and tapestries. In exchange Margaret got the town of Rupelmonde, giving her part of the tolls and custom duties. Philip bore half the cost of repairing the castle in the city and the mill as well.

Philip’s hunting castle in Le Quesnoy

Philip also purchased the Wissekerke Castle in Bazel near Rupelmonde from the Vilain family in 1498 and gave to Philippa, who rebuilt the old castle and made it comfortable place of her own, with a park and a lake around it. But the court of Philip and Philippa did much more then hunting and rebuild palaces. Erasmus was not the only humanist who enjoyed the patronage and an influx of humanists from France, Italy and Germany gathered in Ghent, Bruges, and Brussel over the years.

Among these was Jacques Lefévre d’Étaples, a French theologian who grace the court between 1502-6 until he returned to France and later became a favourite of the king. Johannes Stöffler, a German mathematician, astronomer and professor also visited the court once, presenting the duke and duchess with a collection of his writings. Archduchess Anne gifted her brother with De Verbo Mirifico (The Wonder-Working Word) by Johann Reuchlin in 1497 and books by Marsilio Ficino, a great Italian humanist spread in court.

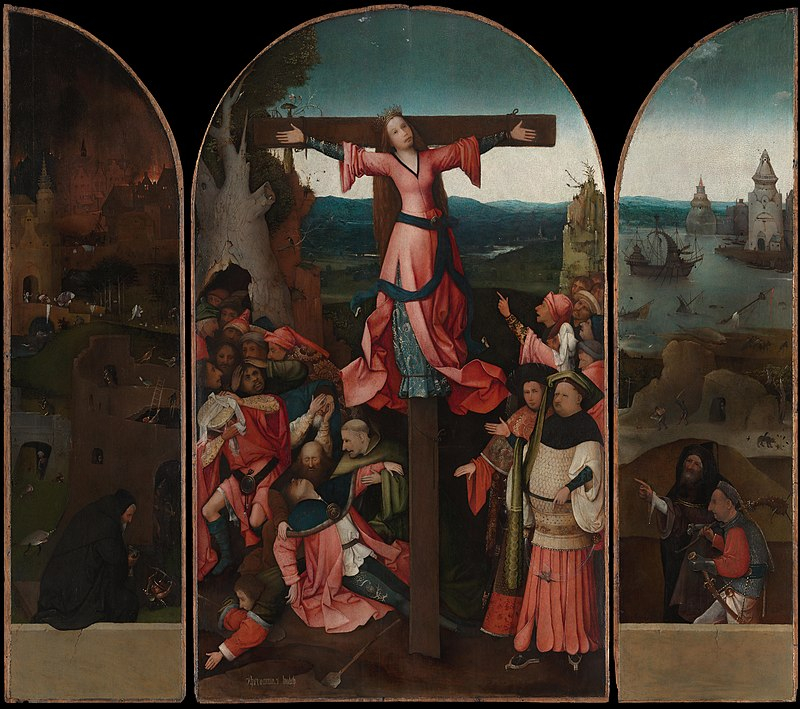

Artists also flocked towards the court. The Flemish painter Jan Gossaert worked actively for Philip after 1506 and others like the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook (whose name is unknown), Albrecht Durer (for a brief while) and Hans Memling (until his death in 1494) enjoyed patronage. Colijn de Coter, Gerard David and Cornelis Engebrechtsz all worked for Philip at one point or another, creating altarpieces and other beautiful paintings. Joachim Patinir and Hieronymus Bosch also found steadfast patrons in the ducal couple. Bosch became a favourite of the duchess, who financed several of his religious works.

The martyrdom of Wilgefortis, an Iberian maid who refused to wed a Moorish man

Made for Duchess Philippa in 1497 by Bosch. Michael Sittow would also work for Philip after 1504, upon the death of Isabel I of Castile.

His friendship with Érard de la Marck, the future bishop of Liegé would go a long way to rebuild the relationship between the duke and Liegé, the city that had been razed by Charles the Bold in 1468. After 1500, the question of Liegé would come up again, with the County of Loon becoming important.

The winter of 1499 saw the whole court holding Christmas celebrations in Gravensteen in Ghent. Philip, Philippa, and all ducal children gathered, with the dowager Margaret of York joining them. Philippa also announced her sixth pregnancy. The last year of the 15th century had proven a good one.

Author's Note: Thus a decade passes in the Grand Duchy of Brabant. Babies, marriage alliances and shipbuilding are bustling. Art, Erasmus and the everyday duties of building a dukedom.

Anne of Burgundy would leave for her imperial bridegroom in 1493 as Archduke Frederick turned fourteen years old. Her entourage left Brussels in late summer to travel to Aachen along with her brother, nephew, and sister-in-law. Little Philippe, Count of Namur (as Charolais was not available anymore) travelled with his family. His parents were determined that his education would include diplomatic matters such as this. Both families would meet up in Aachen with Maximilian and Anne would be received by her new family. Also more importantly, Maximilian was to be elected Holy Roman Emperor in the cathedral of Charlemagne now that he was the ruler of the empire. His successful election in Hungary had given him higher status, even if the first years had been marked with struggles of all kinds.

Philip took one important item with him to Aachen. A coronet owned by his mother Margaret; it had been given by Charles the Bold at the wedding. The coronet itself trimmed with pearls, precious stones and enamelled white roses. The presentation of the dowager’s crown to one of the oldest cathedrals in Europe, constructed by Charlemagne, by the Duke of Brabant carried strong implications. Aachen was the traditional crowning place of the Holy Roman Emperors and the old emperor, The ascension of Maximilian became imminent, as the king of the romans was the title of the imperial successor.

Crown of Margaret of York, Aachen Cathedral

The leading man for the Hapsburg meeting was Eitel Friedrich II, Count of Hohenzollern, one of Maximilian’s most trusted men. He accompanied Maximilian to Aachen, overseeing his entourage. Philip and his family arrived in Aachen in the first week of September, when the trees had just started to turn golden. For Philippa, the old city of Aachen was a beautiful sight, and Philippe was as impressed as a child could be. The Duke and Duchess were greeted at Aachen by Johann Beissel, mayor of the city, who had offered the Aachen Town Hall as residence during their stay. Philip got the entourage and the packings settled in, while Philippa and her ladies rested, afterwards they spent the rest of the evening discussing matters of state with Johann.

The Hapsburg delegation arrived seven days later. The duke and duchess of Brabant greeted him upon his arrival, and Frederick and Anne were introduced later in the evening. Several days of banquets and festivities followed, as Philip gave gift for Frederick. Maximilian in turn gave Philip a bejewelled sword and a richly harnessed stallion in return. More practical matters were also as hand. The renewal of the Burgundian-Hapsburg alliance and matters of trade between realms were discussed. But the core reason for the meeting had been finished and after the two weeks had passed, several days was spent hunting and jousting, to the delight of the people of Aachen. In the last days of September 1493, the ducal couple left Aachen to return to Namur in the low countries.

The Golden Age of Flanders is believed to have started around 1480, and Philip’s reign marked the first part of it. In 1494 Philip had ruled for almost a decade on his own and at the age of twenty-five he was a father of four living children and one unborn. He had become a promising ruler, well acquainted with his people. Philip was an excellent horseman, a skilled linguist and had become an excellent orator (taking after his late father), as well as a good chess player. His education had been managed by the very best scholars in the duchy, both in humanist subjects and science (Philip was a hobby astronomer) and theologian matters. Like his mother he showed interest in the humanist movement and her love for books. He inherited his mother’s height and his father’s stockiness, standing solidly at 6,2 feet. Brown haired and green eyed, with a soft mouth and large ears, Philip made for a handsome man, catching the eyes of the court ladies rather quick. In temper Philip took after his mother: sober manners, determination in his action, an openness to his subjects. From both parents he inherited a restless energy and a sober attire unless there was a grand occasion. Blue, black, or dark clothing was a staple of his wardrobe, warm velvets, or summer silks. Philip favoured efficiency and his household had to move with him, slackers did not last long in his company. His circle of friends consisted of young knights in training, the sons of ducal governors and young noblemen. Many of these men would remain loyal to him for his entire life. From his father he inherited a fierce temper, but it did not appear often. He was also less rash than his predecessor and a better tactician.

The state of the Low Countries in 1493 was one of peace and prosperity. Scars from the years from 1477-81 had healed and Brabant had peace with their neighbours. Philip and Philippa spent a lot of time with agricultural projects, as the loss of the Duchy of Burgundy had left the fruitful fields the areas lost. The damaged fields in Luxembourg and the planes of Brabant had been restored years ago, with resources granted to plant new fields and orchards around the duchy. The farmers in the areas were given a ducal exempt from taxation for a whole year, in return for establishing the new fields. Manufacturers increased production in agricultural equipment after 1480 and the products were distributed to the most needed areas. Philip made several visits to the County of Burgundy, where wine orchards flourished, cheese makers thrived and cattle grazed in the fields. Grainfields popped up all over the duchy from Dóle to Breda for the past fifteen years, becoming a reliable food source for many.

Flanders, Brabant, Hainault, Artois, Picardy and Holland prospered in 1495. The shipyards bustled with activity. Maximilian had given Philip right to import lumber and stone free of custom duties from the German forests since 1486. The lumber also got sent to the shipyards in Holland and Zeeland. Rotterdam in south Holland would become one of the greatest ports in the Low Countries under Philip’s reign.

Rotterdam under the renaissance age

The surplus of lumber was used in rebuilding villages and equipment’s for better living. Amsterdam thrived with builders, rope makers and metalsmiths. The years of peacetime since 1487 had left the duchy with considerable wealth and the efficient government had a surplus of resources. The ducal debt from Charles the Bold had all been paid by 1490, without extra taxation. The cities bustled with productivity, the law officers kept the crime levels to a minimum, new buildings such as churches and farms popped up like mushrooms after rain. One sad note was the death of Jehan van Dadizele in 1498, the lieutenant general of Flanders had passed away. Jehan had been an important member of Philip’s councillors, particularly during times of trouble. Jehan had been interred in the Saint Nicholas Church in Ghent, with the expenses born by the duke. Philip had even ordered a marble effigy to honour him.

With his realm thriving Philip began to look towards the rest Europe’s royal houses to secure foreign allies for the future. In 1495 Philip and Philippa had five living children, nine-year-old Philippe, Count of Namur, Jean born in 1488, Margaretha in 1490, Arnold in 1491 and baby Katherine, born in the spring of 1495. Jean was already betrothed to Marie d’Albret but plans for Philippe’s and Margaretha’s marriages began after Katherine’s birth with strategy in mind. Two ducal delegations left from Bruges in the summer, to London and Copenhagen.

Philip himself was the son of an english mother and the old Anglo-Flemish alliance took priority again. At Christmas in 1495, an agreement was struck between Burgundy and England. Richard III’s and Beatrice of Portugal’s eldest daughter, Beatrice of England, would marry Philippe in 1503 when she turned sixteen. The match was heavily supported by dowager duchess Margaret of York, who had spent all her life since 1468 to maintain the relationship between her homeland and her marriage land. Beatrice had grown into a healthy and active eight-year-old girl. The princess had started her education, held by her mother and selected tutors.

Beatrice of England in 1510

With the arrangements for his heir in place, Philip turned his eye towards the north, to Denmark and King Hans. The relationship between the Dutch merchants and the Hanseatic League had led to the rivalries in the 15th century, with the formerly powerful league of merchants had encountered difficulties of different sorts. A new medium of exchange had been imported from Italy, the double-entry bookkeeping, to control finances. It had been invented in 1492 and Philip had ordered many of the large cities, such as Amsterdam, Antwerp, as well as the Flemish cities to learn it. The Hansa still used silver coins to exchange currency at this point, to their detriment. The building of shipyards in Holland and Zeeland had also been a part of Philip’s strategy to weaken the Hansa, as the league sold ships in every part of Europe. The alliance with the Holy Roman empire meant that the Dutch gained access to direct trade with several of the German princes, cutting out the Hansa as middlemen. The lower costs of trading with the ducal merchants also left the league weaker. Philip pushed hard for dominance against the Hansa with success. The naval wars ensured a monopoly for Polish and Baltic grains for Amsterdam and Antwerp in the 1490s. The match between Copenhagen and Brabant would be another link in Philip’s ambitions. Crown prince Christian was fourteen years old, his potential bride, Margaretha five.

Margaretha of Brabant in 1501

Philip also found a possible bridegroom for baby Katherine in 1496. Jean VI of Brittany had married Eleanor of Gloucester in 1494, and their first son, Richard (also named for Jean’s grandfather Richard, Count of Montfort, Vertus and Étampes) would be born in February. The Duchies of Brabant and Brittany had been allied since Jean’s birth as Charles the Bold had been named godfather before his death that year. Since Francis II of Brittany had broken off the engagement with Anne of Burgundy in 1486, Philip offered Katherine’s hand to baby Richard as a renewal of their alliance and offered to be godfather.

Katherine of Brabant in 1503

Only little Arnold was left without a betrothal in 1496, but as history would turn out his marriage would become every bit as grand as his siblings.

The ducal children were all thriving in 1496, the three youngest living at their grandmother’s court in Malines. The dowager spending most of her time in her palace as well as Binche, one of her dower cities, and Ter Elst, a countryside castle to get away from the dust of the cities. Philippe and Jean resided with the court and travelled with their parents around the duchy, until 1497 when they established their own households in Ghent and Rethel.

Duke Philip met a man in 1492, who would become a life-long friend. A poor scholar named Erasmus who had taken wows in the canonry of Stein in south Holland in 1488. Erasmus had been ordained to the catholic priesthood at the same time the duke was in the area, to issue charters to the shipyards in Rotterdam. Erasmus made the bold move to see the duke and try to gain patronage. After much persuasion, he succeeded in getting an audience in June in Amsterdam. Erasmus had a reputation as a man of letters already before his meeting and while Philip had not read any of his writing, he knew the man’s name.

Erasmus of Rotterdam who barged his way into the ducal household.

What the meeting between Erasmus and the duke consisted of is unknown, but the scholar’s skill in Latin, Greek and erudition seemed to have impressed Philip. Erasmus got a sum of 30 marks by Philip to purchase “necessaries such as writing tools and otherwise”. Erasmus also brough new clothing. A horse and four escorts were also provided by the duke, who intended to put Erasmus to use as a tutor for his eldest children, Philippe, and Jean, now six and four years old. It was high time for them to move past basic learning. Erasmus travelled to Malines, to the court of the dowager duchess Margaret.

Becoming the tutor to the heirs to Brabant was way beyond what Erasmus had hoped for and being given a home in the revered dowager’s palace bore enormous prestige. The duke had trusted him to educate his children. For Erasmus, this was an important win. Dowager Margaret welcomed Erasmus into her home with warmth, the two being very much alike. And the scholar who entered the canonry due to poverty in 1487 would find himself playing chess at evenings with the dowager duchess of Burgundy five years later.

For Margaret of York, dowager Duchess of Burgundy the years since 1486 had been mostly peaceful. The death of her niece Mary of York and firstborn grandson Charles had taken a hard toll on her, but she had recovered afterwards and Philippa of Guelders proved to be an exemplary daughter in law, lifting her spirit from grief. While her son had his hands busy with annihilating the Hanseatic League from the Dutch trading routes and undercutting them with offers, Margaret did not stay idle. Like many women of the times, she took full advantage of widowhood. After her regency was over, she enjoyed a considerable independence with financial security. She raised her grandchildren, stayed updated on politics, and oversaw the administration of her dower lands. In 1493 she had granted Philip her property at Le Quesnoy near the French border, a difficult strategic place for the older dowager to hold. Le Quesnoy lay near Mormail, a vast hunting forest. It suited the active duke and duchess much more than the dowager and the court would hold grand hunts and feasts for many decades. Philip repaired the old castle in the area, using it as a hunting lodge and summer estate, refurbished with Flemish decorations and Castilian carpets and tapestries. In exchange Margaret got the town of Rupelmonde, giving her part of the tolls and custom duties. Philip bore half the cost of repairing the castle in the city and the mill as well.

Philip’s hunting castle in Le Quesnoy

Philip also purchased the Wissekerke Castle in Bazel near Rupelmonde from the Vilain family in 1498 and gave to Philippa, who rebuilt the old castle and made it comfortable place of her own, with a park and a lake around it. But the court of Philip and Philippa did much more then hunting and rebuild palaces. Erasmus was not the only humanist who enjoyed the patronage and an influx of humanists from France, Italy and Germany gathered in Ghent, Bruges, and Brussel over the years.

Among these was Jacques Lefévre d’Étaples, a French theologian who grace the court between 1502-6 until he returned to France and later became a favourite of the king. Johannes Stöffler, a German mathematician, astronomer and professor also visited the court once, presenting the duke and duchess with a collection of his writings. Archduchess Anne gifted her brother with De Verbo Mirifico (The Wonder-Working Word) by Johann Reuchlin in 1497 and books by Marsilio Ficino, a great Italian humanist spread in court.

Artists also flocked towards the court. The Flemish painter Jan Gossaert worked actively for Philip after 1506 and others like the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook (whose name is unknown), Albrecht Durer (for a brief while) and Hans Memling (until his death in 1494) enjoyed patronage. Colijn de Coter, Gerard David and Cornelis Engebrechtsz all worked for Philip at one point or another, creating altarpieces and other beautiful paintings. Joachim Patinir and Hieronymus Bosch also found steadfast patrons in the ducal couple. Bosch became a favourite of the duchess, who financed several of his religious works.

The martyrdom of Wilgefortis, an Iberian maid who refused to wed a Moorish man

Made for Duchess Philippa in 1497 by Bosch. Michael Sittow would also work for Philip after 1504, upon the death of Isabel I of Castile.

His friendship with Érard de la Marck, the future bishop of Liegé would go a long way to rebuild the relationship between the duke and Liegé, the city that had been razed by Charles the Bold in 1468. After 1500, the question of Liegé would come up again, with the County of Loon becoming important.

The winter of 1499 saw the whole court holding Christmas celebrations in Gravensteen in Ghent. Philip, Philippa, and all ducal children gathered, with the dowager Margaret of York joining them. Philippa also announced her sixth pregnancy. The last year of the 15th century had proven a good one.

Author's Note: Thus a decade passes in the Grand Duchy of Brabant. Babies, marriage alliances and shipbuilding are bustling. Art, Erasmus and the everyday duties of building a dukedom.

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 58 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 47 - England from 1523 to 1526 Chapter 48 - Brabant, France and England from 1525 to 1527 Chapter 49 - Spain and the Holy Roman Empire 1523 to 1525 Chapter 50 - Spain and the Holy Roman Empire from 1525 to 1526 Chapter 51 - Brabant, France and the Holy Roman Empire in 1527 Chapter 52 - Spain from 1527 to 1528 Chapter 53 – England in September of 1528 Chapter 54 - Brabant and France in 1528

Share: