You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ravenna, the midwife of Europe

- Thread starter AndreaConti

- Start date

27 The regency

27 The regency

Directly connected to the tradition of the birth of Rome, the Palatine has been a symbolic place throughout its history, used by the highest authorities as an instrument of self-legitimation: residing on the Palatine corresponds to qualifying as powerful, and those who govern preferably settle on the Palatine.

The building complex, located in the center of the city where Augustus' home was located, was begun at the time of Tiberius and continuously enlarged and renovated in the following centuries. It was mainly made up of the Domus Tiberiana and the large structures of the Domus Flavia (the representative sector) and the Domus Augustana (the sector intended for the emperor's residence). But the numerous additions made over the centuries made the entire hill a single, enormous palace: a multifunctional complex equipped with a long series of annexes and services. This true architectural "monster", whose management from the time of Maxentius onwards caused an endless series of headaches for the imperial administration.

Its maintenance was undoubtedly expensive: its residential sections, according to Anicius Severus, were uncomfortable and for the taste of the 5th century, totally out of fashion, so much so that the emperors, when they stayed in Rome, much preferred the palace of the Sexorianus . Honorius himself, despite his antiquarian passion and his desire to establish continuity with the Rome of the first centuries of the Empire, when he visited the city, preferred to reside in the domus, which Cassiodorus defines as simple and Spartan, which he had built in the Horti of Lucullus on the Pincio. [1]

However, for reasons of representation, propaganda and legitimation, being the "place of power" par excellence, the Palatine could not be neglected or abandoned. And this need was very present in Galla Placidia, both for the problems of legitimacy, despite being the heir of two imperial dynasties, the Valentinian and the Theodosian, her being the wife of a barbarian king continued to be unwelcome to a part of the public opinion, as his conflicts with Honorius were known, and because in fact, he had to govern in the name of a child emperor.

Therefore, on October 1st, again for the testimony of Anicius Severus, Galla Placidia

"She summoned the court to what was the home of the ferocious Domitian, enemy of the law and of Christ"

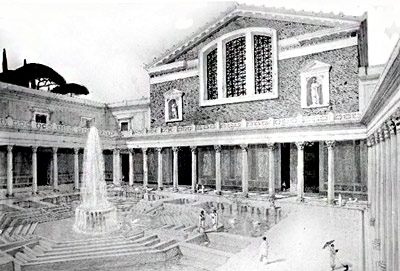

Apart from the judgment on the last of the Flavians, on which modern historians may not even agree, the choice of Galla Placidia demonstrated considerable intellectual sensitivity. In fact, the Domus Flavia was the archetype of all the imperial palaces of Late Antiquity, with its architectural scheme featuring a large reception hall, the Aula Regia, overlooking a peristyle.

A model that, starting from the first decades of the 4th century, was the backbone of many different architectural complexes: palaces of civil power, urban and rural villas, praetoria, bishop's palaces. These are different complexes for specific functions and for the typology of their owners, but their common characteristic is only one: they are all architectures of power, residences of the members of the elites of various kinds placed at the top of the social scale of the late ancient and early Christian world .

Architectures of which I want to underline two aspects. First of all, one of the main characteristics of these complexes consists in their being closed structures, which reveal very little about their internal structure to those outside them. It is only once inside that one perceives their grandeur, through a progression linked to the obligatory path to be followed through the peristyle (and possibly other rooms) to reach the focal point, that is, the apsidal room. In short, the result is that these complexes are essentially 'worlds apart': there are no spaces for mediation between the public and private dimensions, between the palace and the rest of the city, but only a strong instance of ostentation of power and wealth addressed to those who have been chosen to be made part of it, that is, the visitor on duty. In short, a sort of "theatre", useful for the representation of majesty and communion with the Divine that the Empire wanted to give of itself which first Honorius, then Galla Placidia wanted to use as an instrument to combat the centrifugal forces of that organism, undoubtedly complex and diversified, which was the Pars Occidentis.

The second aspect is linked to the fact that this architectural model is based on a perspective of clear social separation, which reflects the rigid and formal hierarchies with which the Empire was organized in the fifth century, as an attempt to dominate the chaos due to the migration of "barbarians", with a preconstituted order, built in the image of the city of God. The third aspect, much more practical, was linked to the fact of its easy defensibility, in an attempt to limit the typically imperial habit of resolving dynastic disputes and politics with murder.

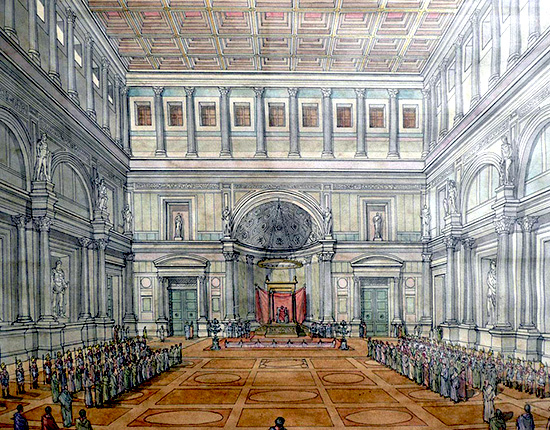

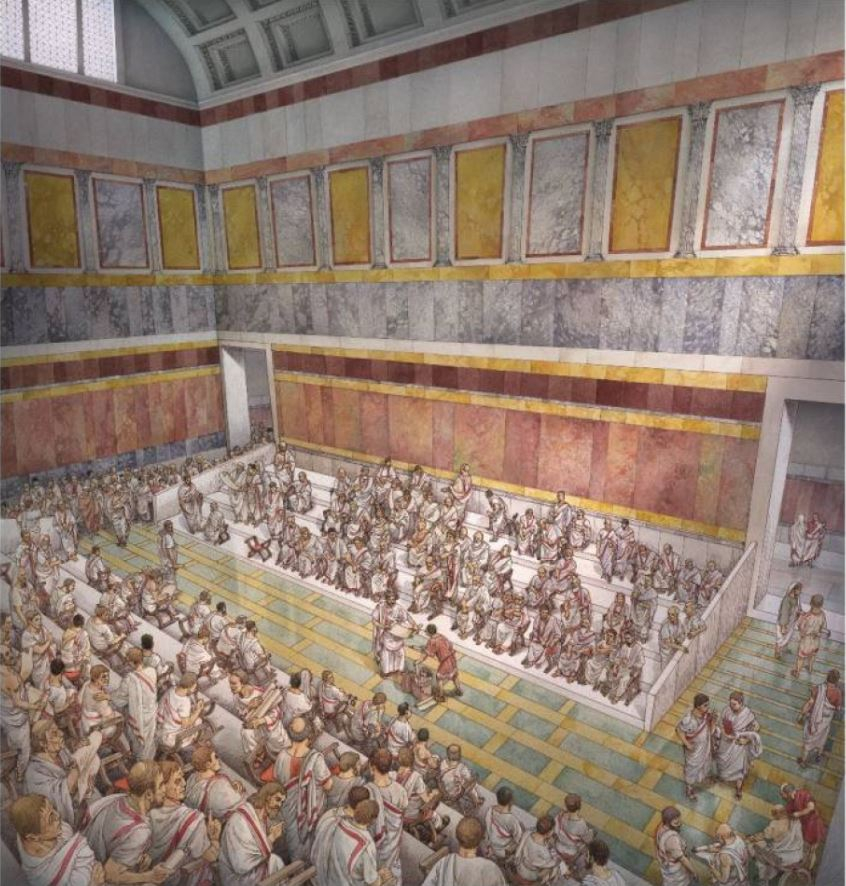

The place chosen by Galla Placidia for the meeting to communicate the composition of the council of regency and for the first imperial salutatio [2] was the so-called Aula Regia, a very large and elevated room, measuring 1,286 square meters of surface area, 41 meters long, 34 meters and approximately 32 meters high, with the walls on the long sides decorated with six mixtilinear niches, framed by porphyry columns supporting a pediment. These aedicules are in turn inserted into a colonnade, jutting out and placed on a high podium, whose columns are in antique yellow and pavonazzetto, with white marble capitals, as are the bases. At the time, each niche contained colossal green marble statues, which both from the testimonies of Anicius Severus and from archaeological excavations, must have represented pagan divinities. Statues which over time have been replaced with portraits of the emperors of the Theodosian dynasty. Above the niches, there are two other orders of columns, which supported a trussed roof hidden by coffers decorated with gold and silver inserts. [3]

The room was rich in stucco decorations, frescoes and marble inlays, which have been modified over time: what remained of what Galla Placidia and Theodosius III saw was a frieze with winged victories and stacks of weapons that recalled Domitian's successes in Germany and the opus sectile floors

The Aula Regia has two doors facing south onto a peristyle with an octagonal fountain in the centre. Between these two entrances, towards the inside of the room, there was a circular arch apse where, at the time of Galla Placida, the throne was placed. The opposite side instead had a single central opening which opened onto a square, the "Palatine Area" cited by ancient sources. The room is located on an elevated podium, placed at the top of a flight of steps that ran along the entire façade of the Domus Flavia. On the sides of the Royal Hall there were two rooms: the "Basilica" with an apse on the left, with a floor in opus sectile with large squares, in which the imperial court gathered and the "Larario" on the right with a tribunal in the background, where it was present the colossus Palatinus, the colossal statue of the emperor, initially Domitian, which was sometimes reworked: the last modification will take place in the IV in which the head will be replaced with the portrait of Gratianus III.

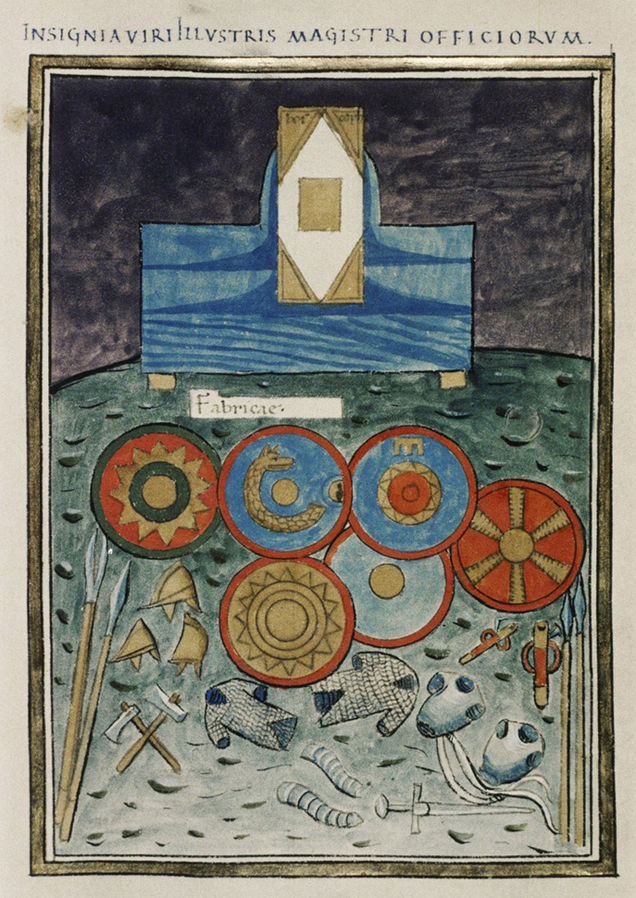

Now the appointment of the regency council and the relative transfer of power also took place thanks to the shrewdness of Honorius, it took place without any particular shocks, even if Galla Placidia and Athaulf were, during the funeral of their half-brother and the coronation of Theodosius III, engaged in lockouts negotiations to distribute seats between their followers and those of the previous emperor. It is interesting to note how the list of offices and roles provided by both Anicius Severus and Cassiodorus follows that of this one in the Notitia Dignitatum, proving that Honorius' book was not considered an imperial oddity, but a guide on how manage the complex imperial bureaucracy.

In particular:

The new administration had to face a series of demanding challenges, both domestic and foreign policy. In the context of internal politics, in addition to preventing some overly ambitious comes, whether Roman or foederatus, from undermining the balance laboriously achieved by Honorius, keeping the imperial accounts in order and combating what today we would define as a phase of economic recession : in the foreign one, once the Rhine limes had been stabilized in some way, there was the question of relations with the Huns, which Galla Placidia hoped, thanks to the mediation of Flavous Aetius, would remain peaceful for as long as possible, of the possession of the Prefecture of Illyricus, a long-standing dispute with Constantinople and the Limes Africanus, with the ever-increasing aggressiveness of the Moorish tribes, which the Comes Bonifacius, which guaranteed its political role, successfully fought, which in the medium term would have required a political solution and not military.

But the immediate question was what the seat of the new imperial court was: whether Athaulf, a convinced supporter of the rhetoric of romanitas and the recovery of the classical tradition and for his relations with Anicius Severus, also because in his opinion the political and military situation of empire, proposed that Galla Placidia remain in Rome, out of habit and because it guaranteed a faster possibility of intervention in the event of a crisis, supported Mediolanum. In the end, since the two spouses could not find a compromise, it was decided to keep her in Ravenna. Thus, on November 18, the imperial procession returned to Ravenna, passing through the Porta Aurea.

In the meantime, at least according to the testimony of Cassiodorus, to reaffirm her continuity with the imperial tradition, Galla Placidia had a new building built on the Palatine, the so-called domus Theodosiana, rediscovered in the nineties, which is configured as a complex consisting of a peristyle overlooked by a large apsed hall, flanked by mixed-line rooms (apses, trichore) and rooms equipped with heating systems. The whole is richly decorated with mosaics and marble decorations dating back to between the 5th and 6th centuries, and the circus was located in the immediate vicinity. To the south we can see what appears to be a second peristyle overlooked by other rooms, in a symmetrical position with the first. This building would essentially have performed representative functions. [4]

[1] Things that also happen OTL

[2] the rite of the audience, in which the emperor received the senators and the equites

[3] Inspired by Filippo Coarelli's description in the book "The houses of power"

[4] OTL is built by Valentinian III and restored by Theodoric

Directly connected to the tradition of the birth of Rome, the Palatine has been a symbolic place throughout its history, used by the highest authorities as an instrument of self-legitimation: residing on the Palatine corresponds to qualifying as powerful, and those who govern preferably settle on the Palatine.

The building complex, located in the center of the city where Augustus' home was located, was begun at the time of Tiberius and continuously enlarged and renovated in the following centuries. It was mainly made up of the Domus Tiberiana and the large structures of the Domus Flavia (the representative sector) and the Domus Augustana (the sector intended for the emperor's residence). But the numerous additions made over the centuries made the entire hill a single, enormous palace: a multifunctional complex equipped with a long series of annexes and services. This true architectural "monster", whose management from the time of Maxentius onwards caused an endless series of headaches for the imperial administration.

Its maintenance was undoubtedly expensive: its residential sections, according to Anicius Severus, were uncomfortable and for the taste of the 5th century, totally out of fashion, so much so that the emperors, when they stayed in Rome, much preferred the palace of the Sexorianus . Honorius himself, despite his antiquarian passion and his desire to establish continuity with the Rome of the first centuries of the Empire, when he visited the city, preferred to reside in the domus, which Cassiodorus defines as simple and Spartan, which he had built in the Horti of Lucullus on the Pincio. [1]

However, for reasons of representation, propaganda and legitimation, being the "place of power" par excellence, the Palatine could not be neglected or abandoned. And this need was very present in Galla Placidia, both for the problems of legitimacy, despite being the heir of two imperial dynasties, the Valentinian and the Theodosian, her being the wife of a barbarian king continued to be unwelcome to a part of the public opinion, as his conflicts with Honorius were known, and because in fact, he had to govern in the name of a child emperor.

Therefore, on October 1st, again for the testimony of Anicius Severus, Galla Placidia

"She summoned the court to what was the home of the ferocious Domitian, enemy of the law and of Christ"

Apart from the judgment on the last of the Flavians, on which modern historians may not even agree, the choice of Galla Placidia demonstrated considerable intellectual sensitivity. In fact, the Domus Flavia was the archetype of all the imperial palaces of Late Antiquity, with its architectural scheme featuring a large reception hall, the Aula Regia, overlooking a peristyle.

A model that, starting from the first decades of the 4th century, was the backbone of many different architectural complexes: palaces of civil power, urban and rural villas, praetoria, bishop's palaces. These are different complexes for specific functions and for the typology of their owners, but their common characteristic is only one: they are all architectures of power, residences of the members of the elites of various kinds placed at the top of the social scale of the late ancient and early Christian world .

Architectures of which I want to underline two aspects. First of all, one of the main characteristics of these complexes consists in their being closed structures, which reveal very little about their internal structure to those outside them. It is only once inside that one perceives their grandeur, through a progression linked to the obligatory path to be followed through the peristyle (and possibly other rooms) to reach the focal point, that is, the apsidal room. In short, the result is that these complexes are essentially 'worlds apart': there are no spaces for mediation between the public and private dimensions, between the palace and the rest of the city, but only a strong instance of ostentation of power and wealth addressed to those who have been chosen to be made part of it, that is, the visitor on duty. In short, a sort of "theatre", useful for the representation of majesty and communion with the Divine that the Empire wanted to give of itself which first Honorius, then Galla Placidia wanted to use as an instrument to combat the centrifugal forces of that organism, undoubtedly complex and diversified, which was the Pars Occidentis.

The second aspect is linked to the fact that this architectural model is based on a perspective of clear social separation, which reflects the rigid and formal hierarchies with which the Empire was organized in the fifth century, as an attempt to dominate the chaos due to the migration of "barbarians", with a preconstituted order, built in the image of the city of God. The third aspect, much more practical, was linked to the fact of its easy defensibility, in an attempt to limit the typically imperial habit of resolving dynastic disputes and politics with murder.

The place chosen by Galla Placidia for the meeting to communicate the composition of the council of regency and for the first imperial salutatio [2] was the so-called Aula Regia, a very large and elevated room, measuring 1,286 square meters of surface area, 41 meters long, 34 meters and approximately 32 meters high, with the walls on the long sides decorated with six mixtilinear niches, framed by porphyry columns supporting a pediment. These aedicules are in turn inserted into a colonnade, jutting out and placed on a high podium, whose columns are in antique yellow and pavonazzetto, with white marble capitals, as are the bases. At the time, each niche contained colossal green marble statues, which both from the testimonies of Anicius Severus and from archaeological excavations, must have represented pagan divinities. Statues which over time have been replaced with portraits of the emperors of the Theodosian dynasty. Above the niches, there are two other orders of columns, which supported a trussed roof hidden by coffers decorated with gold and silver inserts. [3]

The room was rich in stucco decorations, frescoes and marble inlays, which have been modified over time: what remained of what Galla Placidia and Theodosius III saw was a frieze with winged victories and stacks of weapons that recalled Domitian's successes in Germany and the opus sectile floors

The Aula Regia has two doors facing south onto a peristyle with an octagonal fountain in the centre. Between these two entrances, towards the inside of the room, there was a circular arch apse where, at the time of Galla Placida, the throne was placed. The opposite side instead had a single central opening which opened onto a square, the "Palatine Area" cited by ancient sources. The room is located on an elevated podium, placed at the top of a flight of steps that ran along the entire façade of the Domus Flavia. On the sides of the Royal Hall there were two rooms: the "Basilica" with an apse on the left, with a floor in opus sectile with large squares, in which the imperial court gathered and the "Larario" on the right with a tribunal in the background, where it was present the colossus Palatinus, the colossal statue of the emperor, initially Domitian, which was sometimes reworked: the last modification will take place in the IV in which the head will be replaced with the portrait of Gratianus III.

Now the appointment of the regency council and the relative transfer of power also took place thanks to the shrewdness of Honorius, it took place without any particular shocks, even if Galla Placidia and Athaulf were, during the funeral of their half-brother and the coronation of Theodosius III, engaged in lockouts negotiations to distribute seats between their followers and those of the previous emperor. It is interesting to note how the list of offices and roles provided by both Anicius Severus and Cassiodorus follows that of this one in the Notitia Dignitatum, proving that Honorius' book was not considered an imperial oddity, but a guide on how manage the complex imperial bureaucracy.

In particular:

- Iohannes Primicerius, in recognition of his administrative capacity and for the trust he had acquired, for the management of the payment of interest on loans, was appointed Praefectus praetorio Italiae by the senatorial nobility

- Petronius Maximus, to distance him from Rome, limiting his intrigues and in the hope that his ambitions would limit those of the Comes Bonifacius, was appointed Praefectus praetorio Africae

- Priscus Attalus, who unexpectedly was proving to be quite skilled in managing the complex Gallic events, was confirmed as Praefectus praetorio Galliarum

- Anicius Probus, since he was the only one keeping the Senatus of Rome at bay, was confirmed Praefectus urbis

- Flavius Constantius Felix, as a reward for having mediated between Galla Placidia and Honorius, was appointed Magister officiorum

- Paolinus of Pella, given his legal expertise and the expertise that he had developed over the years, navigating the complex bureaucracy of Ravenna, was appointed Quaestor sacri palatii

- Flavius Iunius Quartus Palladius, who had been Iohannes Primicerius' right-hand man, was appointed Questor thesauroum to ensure the continuity of the management of state finances and for his friendly ties with the Comes Bonifacius, who would not have appreciated his political marginalisation.

- Exuperantius of Poitiers, for his diplomatic skills shown in recent years, was appointed and it was the right choice, Magister Barbarorum

- Flavius Aetius was confirmed in the role of Comes domesticorum

- Flavius Castinus was confirmed Magister Praesentialis, who appointed Flavius Astyrius Magister Militum and confirmed Bonifacius Comes Africae, granting him the right to appoint his representative on the regency council. Task that was entrusted to the Roman senator Flavius Avitus Marinianus.

The new administration had to face a series of demanding challenges, both domestic and foreign policy. In the context of internal politics, in addition to preventing some overly ambitious comes, whether Roman or foederatus, from undermining the balance laboriously achieved by Honorius, keeping the imperial accounts in order and combating what today we would define as a phase of economic recession : in the foreign one, once the Rhine limes had been stabilized in some way, there was the question of relations with the Huns, which Galla Placidia hoped, thanks to the mediation of Flavous Aetius, would remain peaceful for as long as possible, of the possession of the Prefecture of Illyricus, a long-standing dispute with Constantinople and the Limes Africanus, with the ever-increasing aggressiveness of the Moorish tribes, which the Comes Bonifacius, which guaranteed its political role, successfully fought, which in the medium term would have required a political solution and not military.

But the immediate question was what the seat of the new imperial court was: whether Athaulf, a convinced supporter of the rhetoric of romanitas and the recovery of the classical tradition and for his relations with Anicius Severus, also because in his opinion the political and military situation of empire, proposed that Galla Placidia remain in Rome, out of habit and because it guaranteed a faster possibility of intervention in the event of a crisis, supported Mediolanum. In the end, since the two spouses could not find a compromise, it was decided to keep her in Ravenna. Thus, on November 18, the imperial procession returned to Ravenna, passing through the Porta Aurea.

In the meantime, at least according to the testimony of Cassiodorus, to reaffirm her continuity with the imperial tradition, Galla Placidia had a new building built on the Palatine, the so-called domus Theodosiana, rediscovered in the nineties, which is configured as a complex consisting of a peristyle overlooked by a large apsed hall, flanked by mixed-line rooms (apses, trichore) and rooms equipped with heating systems. The whole is richly decorated with mosaics and marble decorations dating back to between the 5th and 6th centuries, and the circus was located in the immediate vicinity. To the south we can see what appears to be a second peristyle overlooked by other rooms, in a symmetrical position with the first. This building would essentially have performed representative functions. [4]

[1] Things that also happen OTL

[2] the rite of the audience, in which the emperor received the senators and the equites

[3] Inspired by Filippo Coarelli's description in the book "The houses of power"

[4] OTL is built by Valentinian III and restored by Theodoric

28 The entrance to Ravenna

28 The entrance to Ravenna

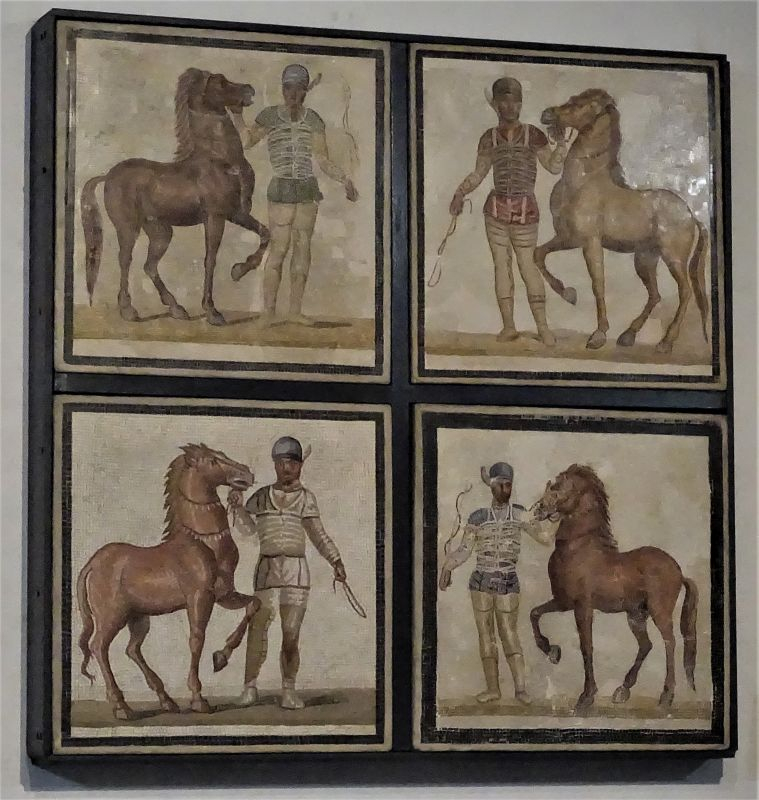

The first task carried out by Galla Placidia, after her entry into Ravenna, was the presentation to the people of the more or less temporary imperial capital: on 25 November, Theodosius III, crowned and dressed in imperial clothes colored purple and woven with gold , accompanied by Galla Placidia and Athaulf, received acclamation from the citizens in the Hippodrome. Then, he inaugurated a series of games and sumptuous ceremonies, organized by the circus factions, which as in Rome were the green, the blue, the white and the red. [1]

In addition to the chariot races, which as in Constantinople and in the other imperial cities of the Pars Occidentis, were an immoderate passion for the people, something that the foederati just couldn't understand, from the testimony of Anicius Severus Athaul was bored to death and had to hold back yawning and avoiding falling asleep during such shows, these celebrations offered Galla Placidia to organize a distribution of gold coins, rations of bread, oil, wine and clothes to testify both the concern of Theodosius III towards the people and the newfound prosperity of the Empire.

Then the imperial family, due to lack of alternatives, moved to the Palatium of Honorius. From Iohordanes' story, a surprising aspect of the late emperor appears, a sort of vain cult of personality, given that the rooms were decorated with statues, mosaics and frescoes portraying him. The Gothic historian tells the story

"The king looked around nervously, having the impression that his deceased brother-in-law continued to observe and judge him from the Underworld"

Now we do not know if this story is true, but there is no doubt that Athaulf, from the beginning, insisted on the construction of a new imperial residence. With the arrival of the court of Athaulf and Galla Placidia from Mediolanum, only the older officials could remember the previous empresses, also because Athaulf, wisely, to avoid nationalist resurgences, maintained a secluded position, like his grandmother Justina, who died in 388 and known for her bad character and for her big arguments with Bishop Ambrogio in Mediolanum.

Ambrose's biographer, Paolino, offers us a lively insight into the clash (Vita Ambrosii, 11):

"He was on the verge of being driven out of the church by a multitude gathered by the power of the Empress Justina, so that an Arian bishop might be ordained not by him but by the heretics. When he was in the presbytery, without caring at all about the riot started by that woman, a of the Arian virgins, more impudent than all the others, climbing into the presbytery grabbed the bishop's robe with the intention of dragging him to the part occupied by the women, so that he would be beaten by them and chased away".

Incidentally, this episode informs us about the existence of virgins also consecrated to the Arian creed and about the division of the naves, below the presbytery, according to the sexes, something which was also taken up by the Gothic church. But even if there had been no more empress regents, after Justina, women of power had not been rare in recent imperial history. Flaccilla, first wife of Theodosius I and Serena, niece of Theodosius and his adoptive daughter, as well as stepmother of Galla Placidia, had maintained this tradition otherwise. In the East, Honorius and Galla Placidia's sister-in-law, Empress Eudoxia, wife of Arcadius, participated in philanthropy and imperial public service, before her daughter Pulcheria took over her duties.

It may be that both took inspiration from the stories that Ambrose told about Helena, mother of Constantine, who in controversy with Justina, glossed over the dark sides of her personality and further undermined the already apologetic portrait provided by Eusebius of Caesarea. Ambrose is in fact the first, among the sources received, to attribute the inventio crucis [2] to Helen, so much so that he dedicated an excursus of De obitu Theodosii [3]to her. In his re-enactment of the event, the bishop of Milan leaves out any other news about the journey to the East to concentrate on what he presents as the very purpose of the journey: the search for the sacred wood. Eager to provide her son with divine help that will protect him from her danger, Helen hurries towards Jerusalem. She finds the place of the crucifixion cluttered with debris and dramatically opposes the devil, proposing herself as a new Mary: just as she, by generating him, showed Christ to humanity, she, by finding the cross, will show his resurrection. After having recognized the right cross thanks to the writing placed by Pilate, the sovereign also searches for and finds the nails of the crucifixion which she places one in a diadem and the other in the horse's bridle, thus making an ancient prophecy come true.

Placed as it is in the context of the funeral oration for Theodosius, the excursus serves Ambrose to justify the right of the eleven-year-old Honorius to the kingdom in the name of that hereditas fidei which, symbolized by the transmission of the nails, is the principle on which, from Constantine onwards, the transmission of a power that is legitimized precisely by faith is founded. Idea, of the Emperor as difensor fidei, which will be used quite speciously by Honorius and more coherently by Galla Placidia, to justify their activism in ecclesiastical affairs

Mother of the first Christian emperor, Helena is the one who establishes this new criterion of succession: the physiognomy of the relationship with her son is significantly modified, because it is no longer Helena who depends on Constantine, but Constantine who is lucky to have such a mother, a great woman that she found much more to offer him than she could receive from him. Model that of Helen, who in addition to inspiring Galla Placidia, who, as we will see, to silence Athaulf's complaints, will replicate the imperial complex of the Sexorianus in Ravenna, including the Palatine Basilica of Santa Croce, [4] will also be an example for Athenaide Eudocia, the wife of Theodosius II, who in political difficulties in that den of vipers that was the court of Constantinople, was able to exploit to her advantage the positive repercussions in terms of image obtained with her first pilgrimage to the Holy Places. She returned there forever after falling into disgrace in 443, she dedicated herself to the construction of sacred buildings, in such a successful mimesis of Helen that it earned her the attribution of the inventio crucis in a 7th century Coptic legend

Precisely because of these proceedings, for the military support of Flavius Castinus and Aetius and for the presence of Athaulf's Gothic troops in Mediolanum, ready to intervene in case of protests, the authority of the Augusta and the imperial family in Ravenna was immediately unchallenged . The administrative machine, reformed, oiled and perfected by Honorius, immediately became operational, supported by the bureaucrats and notaries, chosen by the previous emperor, who helped to define, apply and record every decision of the regent. Court officials, often eununchs, knew how to organize the ceremonial aspects of imperial administration and were able to adapt them to suit a female role. The fundamental aspect is that there was an emperor and in his name, the government could continue even under the direction of a woman and a Goth. This is vividly described by Anicius Severus who describes this scene to us

"Emperor Theoudosius was sitting on two purple cushions, so as not to make him fall from the imperial throne, with on the right the seat on which his mother was sitting, who held his hand and cheered him up with sweet words, and on the left the seat in which, dressed in splendid armor, sat the father, who observed with a severe gaze the high officials and the protectores who were standing in the places that the late Honorius had assigned to them, as if to invite them to carry out their duties with diligence"

Coins, both gold and bronze, minted from the name of Galla Placidia and Theodosius III show the profile of Augusta portrayed on the recto and represent her sitting on a throne with her feet on a cushion and her arms crossed over her breasts on the towards. Although this image is a modified version of the coins commemorating male rulers, it shows the empress seated on the throne with the inscription Salus Rei Publica. [5] This symbolic association had been introduced by Empress Eudoxia a few years earlier, with the hand of God crowning her on the recto, a great advancement of status for the emperor's wives, also due to the fact that Arcadius was nothing more than an unpleasant slacker , which led Priscus to write [6]

"If the two brothers had exchanged the throne, the West would have fallen and the East would have prospered"

However, through the coins of Galla Placidia, minted in Rome, Ravenna and Mediolanum, and in particular in the bronze ones, used for everyday purchases, the inhabitants of the pars Occidentis, both Roman and foederati, came to know his authority . The first problem that Galla Placidia had to face was finding a compromise with Constantinople for the Illyrycum. Augusta, more pragmatic and less obstinate than her half-brother, knew she was in a weak position compared to Constantinople.

First of all, the Pars Orientis, despite the financial reforms wanted by Honorius, continued to be richer: if Constantinople could avoid barbaric attacks also with diplomacy, which included payments of large quantities of gold and luxury goods such as silk and pepper, while Ravenna had to rely, due to lack of liquidity, exclusively on military force. Furthermore, this wealth was less equally distributed than in the Pars Orientis.

A very well-known fragment of the 5th century Greek historian Olympiodorus of Thebes, handed down in the Bibliotheca by the patriarch Photius, deals with the enormous wealth of the Roman nobility of the 4th-5th century:

He (Olympiodorus) reports that many Roman families annually obtained about 4,000 pounds of gold from their properties, without considering wheat, wine and all other products, the value of which, in the case of sale, corresponded to a third of the gold income. . The families immediately below those in wealth had incomes between 1,500 and 1,000 pounds of gold. He also reports that Probus, the son of Olympius, who held the praetorship in the first year of the Emperor Theodosius III, spent 1,200 pounds of gold; the orator Simmacus – a senator of medium wealth – spent 2,000 pounds on the praetorship of his son Simmacus before the sack of Rome; Maximus, who was among the richest of him, spent 4,000 on his son's praetorship. The praetors offered public games for seven days

Ravenna, to support the costs of a war with Constantinople for the Illirycum, would have had to get further into debt with the Roman senatorial class, increasing its influence, something that Galla Placidia wanted to avoid at all costs. Secondly, with the positive end of the war against the Sasanians, by being able to transfer Theodosius II's troops to the Balkans, Constantinople had rebalanced the military balance of power. Finally, Ravenna had to manage the Hunnic question.

The problem was not Rua, which had stabilized the Balkan border and had given the Empire a single interlocutor, but rather predictable in its needs and in the long run almost reassuring, which favored the diplomatic instrument, only sporadically supported by military pressure, to obtain better economic conditions such as gold subsidies and free market zones and above all a clear line of demarcation between two zones of influence: the one south of the Danube was reserved for the Romans, the one to the north was reserved for the Huns and within the two there was a rigid control over their respective populations. Rua also, thanks to his ties with Flavius Aetius, was a reliable ally of Ravenna.

The problem was Octar, Rua's brother, who had established himself, perhaps as a foederatus, in Pannonia Valeria: the Hun king, in contravention of the pacts, had occupied part of Pannonia Prima and was carrying out raids in Germany, putting in crisis the stabilization work on the Limes Renano carried out by Honorius ; to bring Octar back into the ranks, Ravenna needed military and diplomatic support from Constantinople. Therefore, Galla Placida was very inclined to start negotiations with Theodosius II, when the issue dropped in priority due to the news coming from Africa: the comes Bonifacius had to face a new war with the Moors! [7]

[1] The post is inspired by a chapter in Judith Herrin's book

[2] Discovery of the Cross of Jesus

[3] The funeral oration in honor of Theodosius

[4] Topic of a future post

[5] Salvation of the State

[6] Historian and diplomat of the time, famous for his description of an embassy to Attila's court

[7] We are in the 5th century, problems are never lacking! 😁

The first task carried out by Galla Placidia, after her entry into Ravenna, was the presentation to the people of the more or less temporary imperial capital: on 25 November, Theodosius III, crowned and dressed in imperial clothes colored purple and woven with gold , accompanied by Galla Placidia and Athaulf, received acclamation from the citizens in the Hippodrome. Then, he inaugurated a series of games and sumptuous ceremonies, organized by the circus factions, which as in Rome were the green, the blue, the white and the red. [1]

In addition to the chariot races, which as in Constantinople and in the other imperial cities of the Pars Occidentis, were an immoderate passion for the people, something that the foederati just couldn't understand, from the testimony of Anicius Severus Athaul was bored to death and had to hold back yawning and avoiding falling asleep during such shows, these celebrations offered Galla Placidia to organize a distribution of gold coins, rations of bread, oil, wine and clothes to testify both the concern of Theodosius III towards the people and the newfound prosperity of the Empire.

Then the imperial family, due to lack of alternatives, moved to the Palatium of Honorius. From Iohordanes' story, a surprising aspect of the late emperor appears, a sort of vain cult of personality, given that the rooms were decorated with statues, mosaics and frescoes portraying him. The Gothic historian tells the story

"The king looked around nervously, having the impression that his deceased brother-in-law continued to observe and judge him from the Underworld"

Now we do not know if this story is true, but there is no doubt that Athaulf, from the beginning, insisted on the construction of a new imperial residence. With the arrival of the court of Athaulf and Galla Placidia from Mediolanum, only the older officials could remember the previous empresses, also because Athaulf, wisely, to avoid nationalist resurgences, maintained a secluded position, like his grandmother Justina, who died in 388 and known for her bad character and for her big arguments with Bishop Ambrogio in Mediolanum.

Ambrose's biographer, Paolino, offers us a lively insight into the clash (Vita Ambrosii, 11):

"He was on the verge of being driven out of the church by a multitude gathered by the power of the Empress Justina, so that an Arian bishop might be ordained not by him but by the heretics. When he was in the presbytery, without caring at all about the riot started by that woman, a of the Arian virgins, more impudent than all the others, climbing into the presbytery grabbed the bishop's robe with the intention of dragging him to the part occupied by the women, so that he would be beaten by them and chased away".

Incidentally, this episode informs us about the existence of virgins also consecrated to the Arian creed and about the division of the naves, below the presbytery, according to the sexes, something which was also taken up by the Gothic church. But even if there had been no more empress regents, after Justina, women of power had not been rare in recent imperial history. Flaccilla, first wife of Theodosius I and Serena, niece of Theodosius and his adoptive daughter, as well as stepmother of Galla Placidia, had maintained this tradition otherwise. In the East, Honorius and Galla Placidia's sister-in-law, Empress Eudoxia, wife of Arcadius, participated in philanthropy and imperial public service, before her daughter Pulcheria took over her duties.

It may be that both took inspiration from the stories that Ambrose told about Helena, mother of Constantine, who in controversy with Justina, glossed over the dark sides of her personality and further undermined the already apologetic portrait provided by Eusebius of Caesarea. Ambrose is in fact the first, among the sources received, to attribute the inventio crucis [2] to Helen, so much so that he dedicated an excursus of De obitu Theodosii [3]to her. In his re-enactment of the event, the bishop of Milan leaves out any other news about the journey to the East to concentrate on what he presents as the very purpose of the journey: the search for the sacred wood. Eager to provide her son with divine help that will protect him from her danger, Helen hurries towards Jerusalem. She finds the place of the crucifixion cluttered with debris and dramatically opposes the devil, proposing herself as a new Mary: just as she, by generating him, showed Christ to humanity, she, by finding the cross, will show his resurrection. After having recognized the right cross thanks to the writing placed by Pilate, the sovereign also searches for and finds the nails of the crucifixion which she places one in a diadem and the other in the horse's bridle, thus making an ancient prophecy come true.

Placed as it is in the context of the funeral oration for Theodosius, the excursus serves Ambrose to justify the right of the eleven-year-old Honorius to the kingdom in the name of that hereditas fidei which, symbolized by the transmission of the nails, is the principle on which, from Constantine onwards, the transmission of a power that is legitimized precisely by faith is founded. Idea, of the Emperor as difensor fidei, which will be used quite speciously by Honorius and more coherently by Galla Placidia, to justify their activism in ecclesiastical affairs

Mother of the first Christian emperor, Helena is the one who establishes this new criterion of succession: the physiognomy of the relationship with her son is significantly modified, because it is no longer Helena who depends on Constantine, but Constantine who is lucky to have such a mother, a great woman that she found much more to offer him than she could receive from him. Model that of Helen, who in addition to inspiring Galla Placidia, who, as we will see, to silence Athaulf's complaints, will replicate the imperial complex of the Sexorianus in Ravenna, including the Palatine Basilica of Santa Croce, [4] will also be an example for Athenaide Eudocia, the wife of Theodosius II, who in political difficulties in that den of vipers that was the court of Constantinople, was able to exploit to her advantage the positive repercussions in terms of image obtained with her first pilgrimage to the Holy Places. She returned there forever after falling into disgrace in 443, she dedicated herself to the construction of sacred buildings, in such a successful mimesis of Helen that it earned her the attribution of the inventio crucis in a 7th century Coptic legend

Precisely because of these proceedings, for the military support of Flavius Castinus and Aetius and for the presence of Athaulf's Gothic troops in Mediolanum, ready to intervene in case of protests, the authority of the Augusta and the imperial family in Ravenna was immediately unchallenged . The administrative machine, reformed, oiled and perfected by Honorius, immediately became operational, supported by the bureaucrats and notaries, chosen by the previous emperor, who helped to define, apply and record every decision of the regent. Court officials, often eununchs, knew how to organize the ceremonial aspects of imperial administration and were able to adapt them to suit a female role. The fundamental aspect is that there was an emperor and in his name, the government could continue even under the direction of a woman and a Goth. This is vividly described by Anicius Severus who describes this scene to us

"Emperor Theoudosius was sitting on two purple cushions, so as not to make him fall from the imperial throne, with on the right the seat on which his mother was sitting, who held his hand and cheered him up with sweet words, and on the left the seat in which, dressed in splendid armor, sat the father, who observed with a severe gaze the high officials and the protectores who were standing in the places that the late Honorius had assigned to them, as if to invite them to carry out their duties with diligence"

Coins, both gold and bronze, minted from the name of Galla Placidia and Theodosius III show the profile of Augusta portrayed on the recto and represent her sitting on a throne with her feet on a cushion and her arms crossed over her breasts on the towards. Although this image is a modified version of the coins commemorating male rulers, it shows the empress seated on the throne with the inscription Salus Rei Publica. [5] This symbolic association had been introduced by Empress Eudoxia a few years earlier, with the hand of God crowning her on the recto, a great advancement of status for the emperor's wives, also due to the fact that Arcadius was nothing more than an unpleasant slacker , which led Priscus to write [6]

"If the two brothers had exchanged the throne, the West would have fallen and the East would have prospered"

However, through the coins of Galla Placidia, minted in Rome, Ravenna and Mediolanum, and in particular in the bronze ones, used for everyday purchases, the inhabitants of the pars Occidentis, both Roman and foederati, came to know his authority . The first problem that Galla Placidia had to face was finding a compromise with Constantinople for the Illyrycum. Augusta, more pragmatic and less obstinate than her half-brother, knew she was in a weak position compared to Constantinople.

First of all, the Pars Orientis, despite the financial reforms wanted by Honorius, continued to be richer: if Constantinople could avoid barbaric attacks also with diplomacy, which included payments of large quantities of gold and luxury goods such as silk and pepper, while Ravenna had to rely, due to lack of liquidity, exclusively on military force. Furthermore, this wealth was less equally distributed than in the Pars Orientis.

A very well-known fragment of the 5th century Greek historian Olympiodorus of Thebes, handed down in the Bibliotheca by the patriarch Photius, deals with the enormous wealth of the Roman nobility of the 4th-5th century:

He (Olympiodorus) reports that many Roman families annually obtained about 4,000 pounds of gold from their properties, without considering wheat, wine and all other products, the value of which, in the case of sale, corresponded to a third of the gold income. . The families immediately below those in wealth had incomes between 1,500 and 1,000 pounds of gold. He also reports that Probus, the son of Olympius, who held the praetorship in the first year of the Emperor Theodosius III, spent 1,200 pounds of gold; the orator Simmacus – a senator of medium wealth – spent 2,000 pounds on the praetorship of his son Simmacus before the sack of Rome; Maximus, who was among the richest of him, spent 4,000 on his son's praetorship. The praetors offered public games for seven days

Ravenna, to support the costs of a war with Constantinople for the Illirycum, would have had to get further into debt with the Roman senatorial class, increasing its influence, something that Galla Placidia wanted to avoid at all costs. Secondly, with the positive end of the war against the Sasanians, by being able to transfer Theodosius II's troops to the Balkans, Constantinople had rebalanced the military balance of power. Finally, Ravenna had to manage the Hunnic question.

The problem was not Rua, which had stabilized the Balkan border and had given the Empire a single interlocutor, but rather predictable in its needs and in the long run almost reassuring, which favored the diplomatic instrument, only sporadically supported by military pressure, to obtain better economic conditions such as gold subsidies and free market zones and above all a clear line of demarcation between two zones of influence: the one south of the Danube was reserved for the Romans, the one to the north was reserved for the Huns and within the two there was a rigid control over their respective populations. Rua also, thanks to his ties with Flavius Aetius, was a reliable ally of Ravenna.

The problem was Octar, Rua's brother, who had established himself, perhaps as a foederatus, in Pannonia Valeria: the Hun king, in contravention of the pacts, had occupied part of Pannonia Prima and was carrying out raids in Germany, putting in crisis the stabilization work on the Limes Renano carried out by Honorius ; to bring Octar back into the ranks, Ravenna needed military and diplomatic support from Constantinople. Therefore, Galla Placida was very inclined to start negotiations with Theodosius II, when the issue dropped in priority due to the news coming from Africa: the comes Bonifacius had to face a new war with the Moors! [7]

[1] The post is inspired by a chapter in Judith Herrin's book

[2] Discovery of the Cross of Jesus

[3] The funeral oration in honor of Theodosius

[4] Topic of a future post

[5] Salvation of the State

[6] Historian and diplomat of the time, famous for his description of an embassy to Attila's court

[7] We are in the 5th century, problems are never lacking! 😁

29 De Africa

29 De Africa

If for the imperial court of Ravenna the phenomenon of climate change may have been very unclear, beyond the rhetorical complaints of "the sun warms less than in the past" and "the winter days are increasingly longer", its effects on Mediterranean agriculture were evident. The lower evaporation was in fact changing the rainfall regime, with drier summers and rainfall essentially concentrated between January and March. Therefore, to be efficient, agriculture was beginning to require significant investments in hydraulic works, capable of exploiting both surface water and aquifers, favoring large senatorial-owned estates over small farmers. Phenomenon that was changing the agricultural landscape in Sicily, Sardinia and Calabria. Forestry, with the production of pitch, the breeding of pigs, the cultivation of vines and fruit trees were progressively replaced by sheep breeding and the production of oil and wheat. [1]

The greatest impact, however, was being had in the African provinces, which from 324, the year in which its taxpayers who already bore the brunt of Rome's ration supply in terms of contributed quantities of oil and grain and liturgical services, was saddled with the burden of paying the wheat contribution previously provided by Egypt, for the distributions of Rome, Mediolanum to which, at the time of Honorius, those for Ravenna were also added

But how significant was this wheat contribution? This topic is very divisive for scholars of the late ancient and early Christian ages. They range from maximalist theses dating back to J. Beloch's idea according to which the royalties, and in particular the wheat rent, were sufficient to satisfy the fundamental needs of the imperial capitals, up to hyperminimalist theses which understand the rent as the exclusive contribution of a plebeian extremely reduced rations: a few tens of thousands of rations. Currently, but things could also change in the coming years, a sort of "moderate minimalism" predominates: scholars believe that the late antique canons were intended to essentially cover the needs of the ration plebs, estimated in the 5th century, considering Rome, Mediolanum and Ravenna , in approximately 250,000 beneficiaries, while the smaller quotas, in particular of wheat and wine, were used for public payments, or poured into circulation at a free price, or used during food supply emergencies. Instead, they tend to exclude, also due to the economic interests of the senatorial class, the existence of regular circuits of foodstuffs sold at political prices coexisting with free distributions, which are not attested either in Rome, Mediolanum and Ravenna, or in Constantinople. In any case, there is no doubt that, in normal situations, the fees calmed the market of fundamental commodities and constituted an indispensable support for a significant part of the population of the imperial capitals. For wheat in particular, considering the diet and calorie needs of an adult, it is reasonable to double the real number of beneficiaries. [2]

The greater fiscal burden, in the face of the decrease in agricultural productivity, as well as increasing the discontent of the African subjects, led the Empire, between the 4th and 5th centuries, to impose a sort of militarization in the collection of wheat rents: according to the agronomist Palladius, in the African regions the peak of the wheat season began at the end of June and ended in July, while the harvest of oil production was concentrated in November. The tributary calendar spanned two solar years with a variable start between the different areas of the empire: July 1st in Egypt, September 1st in other provinces. In Africa the fiscal year ran from November to October and, starting from 364-365, was divided into four months: November-February, March-June, July-October. so, as a rule, taxpayers could deliver the species annonariae to the fiscal horrea of their district in a single solution or in three solutions, with the obligation to pay at least 1/3 of the amount due after the calends of March (evidently to collect the 'new oil) and the rest after the calends of July (evidently to capture the new wheat). for emphyteutic funds the fiscal year began in January and the first payment, also due after the calends of March (and therefore important for oil), was 1/660.

These deadlines seem to reflect an organization of fiscal perception tending to guarantee a continuous flow of foodstuffs and to maximize the receptivity of the ration horrea network by distributing the delivery throughout the year and implementing a rapid movement of the stocks leaving the smaller warehouses towards the larger warehouses . Since the role of local authorities is fundamental for this aspect, two clarifications are appropriate. The laws hinge the provincial collection in the cities' horrea fiscalia, [3]reserved for the exclusive use of the state, which centralized perception. In fact, the first phase of the collection, carried out by praepositi pagorum et horreorum appointed by the curiae, also took place, and perhaps to a primary extent, in warehouses distributed throughout the territory from which the foodstuffs were subsequently transferred to the cities. This method is evident in the instructions of the epigraphic constitution of Trinitapolis of Valentinian I, specifically referring to southern Italy but adhering to regulations of general scope. And in fact also in the "Tariff of Carthage", referring to the proconsular and attributable to the emperor himself, the toponyms of 27 tax districts bear three different names: fundi, civitates, pars territoriali [4] (the latter term perhaps to be understood as equivalent to pagus)[5]. It is also not excluded that, for reasons of logistical convenience, in some locations the perception took place at the stations close to the coast and that therefore these loads were not forwarded from the territory to the city but taken directly to the ports of embarkation. This reconstruction is supported by general provisions on the obligation of the presence of sample measurements in the stations [6]

Obviously, Honorius, with his passion for micro management, could not fail to have his say in such an organization: he introduced the institution of tax quarters and quarterly payments (tripartita inlatio), payment receipts that the taxpayer had to forward to the municipal tabularii [7]and a series of rather punitive measures against tax evaders and officials who stole part of the grain and other commodities: in the best case scenario, they would end up working in the Sardinian mines for life, in the worst case, well, Honorius had vented his anger in penis several sadistic fantasies!

This increase in the tax burden and the abandonment of the less productive fields, transformed into pastures, on which, a common phenomenon with other areas of the Pars Occidentis, the urban bourgeoisie was investing, requiring less start-up costs compared to agricultural cultures, were associated with the effects of competition from Iberian and Sicilian oil, the only product thanks to which the Mediterranean farmer entered the commercial circuits, and from Sardinian granite and Luni marble, whose quarries were beginning to be exploited "industrially" by the Anicia gens, and which in Italy and Gaul were progressively replacing African stones. All this, in addition to a moderate recession, was causing a strong reduction of wealth in the African provinces, creating a sort of Matthew effect, with the rich get richer and the poor get poorer: thus farmers deprived of their land and laborers often willingly abandoned the imperial territories, to go to the Mauri. The Mauri, in turn, due to the drying up of their pastures, were forced to migrate towards the Mediterranean coasts,

These gentes externae of the African regions, like most barbarians in the ancient world, unfortunately did not leave written documents narrating historical events from their point of view. On the other hand, Greek and Roman authors observed these tribes through a distorting lens, describing them in a stereotypical, generic and strongly characterized way: the Mauri appear as alien, exotic, strange, aggressive and alien to any form of civilization.

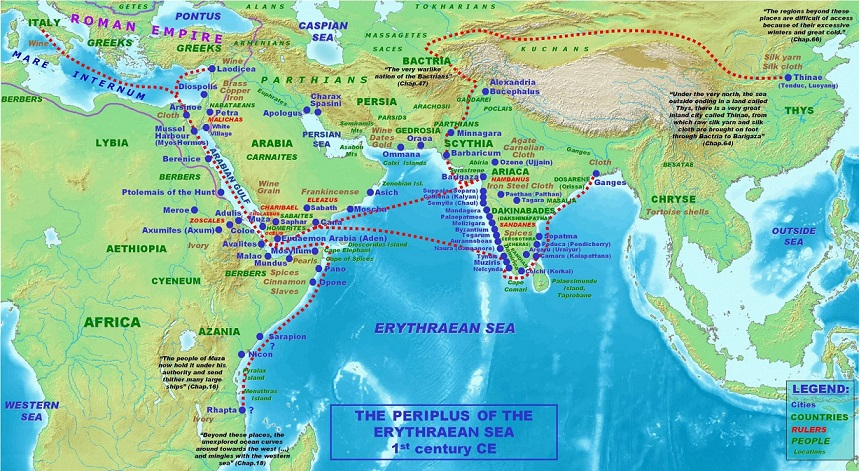

Only the sources from the 6th century, in which the Mauri appear to have been integrated into the system of imperial power, which hand down the previous oral traditions, lead us to believe that, between the 3rd and 4th centuries, this people made great migrations from the east towards the west. Among other things, the name Mauri therefore designated different realities: there were the Frexes south-east of Byzacena, the peoples of Aurès in Numidia and a nebula of clans settled in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. It is estimated that they were not very numerous people, but that their population had grown thanks to the fleeing peasant masses, who, in addition to changing their demographics and their economy, had accentuated the phenomenon of cultural "Romanization". From the testimonies of the time, for example, we know that the tribal leaders spoke a dignified Latin: the Mauri of Byzacena and Numidia inhabited the mountains and practiced agriculture, while those of Tripolitania were, instead, camel drivers, nomads, dedicated to breeding and settled in the pre-desert area and which were enriched by trans-Saharan trade between the Mediterranean coast and equatorial Africa, which was growing in importance, due to Constantinople's control of the Red Sea ports, from which they departed, in addition to the maritime routes and trade routes to India, including those headed towards southern Africa, as described in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, which, due to the amount of information it contains, is a sort of guide for traders and travellers. The author does not limit himself to a merely geographical description, but adds information of a political, anthropological and, above all, economic nature: for each port encountered, the marketable goods therein are described, both imported and exported, the best times to sail along a given route and those suitable for sailing, and all that information that can prove useful for making profits and good business. [8]

Of the two circumnavigation routes, the one that runs along Africa takes up the least space, and for this reason it could give the impression of being a secondary route. However, its importance within the Eritrean sea should not be underestimated, since from the ports of East Africa it was possible to purchase luxury goods, albeit of lesser quality, without having to undertake ocean voyages to India. This favored those who only had small or medium-sized boats at their disposal. The route involved skirting the continent from the Egyptian ports on the Red Sea to the port of Rhapta, near today's Dar es Salaam, in Tanzania and the southern limit of the lands known to the author of the Periplus. In between, the merchants found themselves faced mainly with small centers led by local leaders, especially along the coasts of Somalia (traditionally identified as the legendary country of Punt), and with primitive populations, located in today's Sudan and organized into tribes: the Ichthyophagi (“Fish Eaters”), the Agriofagi (“Wild Animal Eaters”) and the Moschofagi (“Cattle Eaters”) .

The only exception is the domains of Zoskales, a greedy and ambitious king but expert in reading and writing the Greek language and the city of Axomites (name of the circumnavigation of Axum). The products obtainable were divided into two categories: those of animal origin, ivory and turtle shells first and foremost, and a good number of spices and aromas, such as cassia, incense and myrrh. In exchange, inexpensive clothes, utensils, foodstuffs and, in general, products capable of satisfying mostly basic products were exchanged (or, more rarely, purchased) given that in most commercial ports local merchants and lords could not afford big expenses

Returning to the Mauri, Corippus, in Iohannis, [9] recalls how these people, how the Bagaudes had already represented a problem in the tetrarchic period and Maximian had fought against them, without success, around 298 AD. A hot season in relations between the Romans and the Mauri seems to have opened in the 4th century AD, when the latter had become a sort of endemic threat, with their seasonal incursions into Africa, which intensified after the death of Julian the Apostate . These were groups of raiders of around 2000 units, who avoided clashes in open fields but were able to surprise their adversaries with their lightning-fast appearances and disappearances. Relations between Rome and these "barbarians of Africa", however, were complex and were certainly not limited to military conflicts. It is known, in fact, that over the centuries, the border policy implemented by the Empire involved ever greater collaboration with those who lived beyond the limes. Therefore, it seems that the Mauri were also, for example, enlisted to defend the frontier or were allowed to work as laborers in the Roman regions, another phenomenon that contributed to their Latinization.

Precisely the contact with Rome would have favored, at least for some social groups, an increase in wealth, leading to the emergence of local warlords. These "warlords" exploited the prestige, including economic, deriving from relations with the Empire, in the military and political spheres, imposing their authority on their people and making personal alliances with the administration, a phenomenon that led to the transition from chiefdom and real organized kingdoms, with political and territorial ambitions and capable of mobilizing armies that Anicius Severus, probably exaggerating, estimated at 30,000 soldiers, armed essentially with javelins, bows and arrows and short swords.

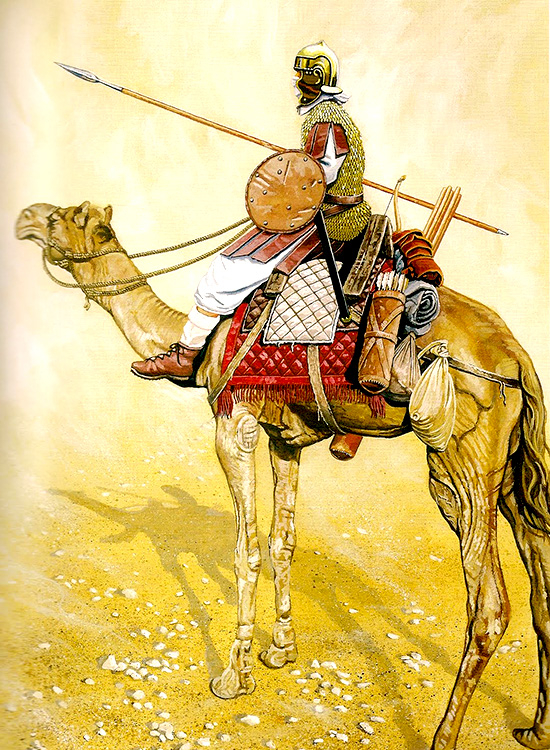

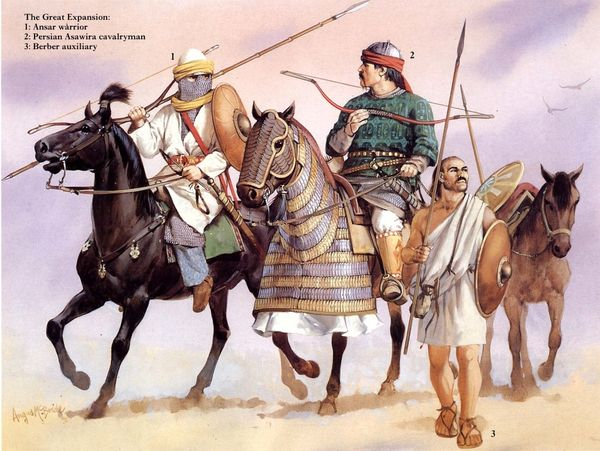

Now the Comes Bonifacius had not remained idle in the face of this threat: in addition to developing, through subsidies and political and commercial agreements, its own network of clientele among the Mauri, applying the traditional policy of divide and conquer, it had initiated two military reforms, which will have enormous impact in the future. The first concerned the army: despite his esteem for Flavius Castinus, Bonifacius was quite clear that his reform had been conceived to fight on the European scene, not on the African one, where even greater mobility was needed and where the problem of heat and the lack of water made the use of armor uncomfortable. [10]

From what Anicius Severus tells, which unfortunately deals with the African events in a very marginal way, the infantry of the Comes Bonifacius, which the Latin historian says was inspired by the Macedonian phalanx, was made up of lancers, armed with a 5 meter pike, given that Anicius Severus says it was two-thirds as long as the sarissa, which could be held with one hand and by the carnifex, which from recent findings, a sort of scimitar, of Hunnic inspiration, 60 centimeters long. The defensive armament consisted of shields and leather armour, covered by a white tunic and a rounded helmet, of Sasanian inspiration, often covered by a turban, as protection from the desert winds. The lancers were associated with the so-called Spatax, Gothic or Burgundian auxiliaries, chosen for their stature and physical prowess, armed with a long spatha, which in addition to challenging the Mauri leaders and champions to a duel, had to break with the cut through the enemy lines, thus making the task easier for the spearmen. Perhaps exaggerating Anicius Severus tells

"They mowed down their enemies like farmers mowed down ears of wheat"

Behind the lancers and the Spataxes, Bonifacius deployed the archers, who had adopted the same composite bow as the Mauri. The cavalry was armed with contarion, a variant of the Kontos, a two-pronged spear, four meters long, which unlike the original could be used with just one hand, thanks to a special housing placed under the armpit, and of a Hunnic sabre; unlike infantrymen, they wore a lorica hamata, a coat of mail. Upon completion, the logistics of the troops were entrusted to specific camel departments.

The other innovation was in the start of a specific process of fortification of the African provinces, which Honorius, always attentive to budgetary needs, did not complain about, aware of its importance. It may seem strange, but until the beginning of the 5th century, very few African cities - archeology seems to show only Cherchell and Tipasa - were equipped with city walls. To the south, however, along the limes, whose route had been more or less defined at the time of the Severi, from Tripolitania to Mauretania Tingitana, military camps and forts (castra and castella) had multiplied and sometimes continuous defense lines along which stood more modest works such as the Fossatum Africae, a ditch whose width varies from 4 to 10 metres, and which can reach a depth of 1-1.5 meters on one side of the ditch or on both sides, depending on sometimes replaced by a dry stone wall, integrated with watchtowers, built in the times of Constantine. [11] Comes Bonifacius completely reversed this approach. With a lot of pragmatism, the appearance of the fortifications built varies greatly: the restricted walls, the citadels and even the forts (Madauros, Algeria) were located in the heart of the ancient cities and implied a subversion of the urban plan with a preliminary destruction or adaptation of monuments and with the creation of terraces, worth that is, of areas left free on a slight slope around the city walls. Other fortresses, however, were outside urban centers, even if they were built, as in Timgad or Ksar Lemsa, on much older buildings. Purely utilitarian and rapidly constructed architecture, the fortifications had no aesthetic pretensions. To reduce time and costs, the construction technique favored, in fact, the reuse of stripped ashlars, which came from destroyed buildings or necropolises (often many blocks retain inscriptions), carelessly superimposed in irregular rows, without mortar, to form the two external walls which were filled on the inside with rubble.

The expertise of the Roman military engineers was exercised rather on the routes, often irregular, given the need to take into account topographical needs in the walls, generally restricted, strictly geometric for the forts, with two important variations, depending on the size: the quadriburgium, with four towers at the corners (Ksar Lemsa), or the rectangular fortress with intermediate towers (of the Timgad type). The type of towers (especially with a square plan) protruding from the wall, the doors (open in a tower or framed between two towers, often equipped with successive closures, doors and shutters), the patrol paths frequently supported by arches, the access stairs to the walkways, the arrangement of the loopholes - of which few traces remain - belong to the normal acquisitions of military techniques of the time and do not differ much from the creations known in other provinces. However, the ignorance of polyorcetics and the absence of siege material on the part of the Moors led to a certain economy of means: in fact, the moats and external walls were missing. The internal layout is known only in the case of the few fortresses in which excavations have been carried out: in Timgad these are classic-type quarters, intended for a garrison, while in Ksar Lemsa the quarters seem more summary and heterogeneous. A fortress (Timgad) and at least one citadel (Ammaedara/Haidra) contain two distinct garrison chapels, probably one intended for the Nicaeans and one for the Arians.

This state activity of fortification was also imitated by the private initiative of many landowners of the senatorial class, who protected their villas with walls without towers and built a large number of forts measuring 10 to 20 m on each side, often without doors (and therefore accessible only on the upper floor), but sometimes closed, with a system that is both effective and economical, by a "wheel" door in the rural area of Tripolitania, in the south of Byzacena and Numidia and in the inland cities, where they served as a support point for more substantial fortresses.

Following these tactical and strategic choices, the population was able to take refuge in the fortresses and the war, instead of a sequence of large battles, was a sequence of raids and limited clashes on both sides, which however had the impact of drastically reducing the direct supply of wheat from Africa to Italy. To avoid revolts by the urban plebs of Rome, Mediolanum and Ravenna, Galla Placidia, in January 424 had to extend the frumentarium fee to Sicily, Calabria, Sardinia: in exchange, the Roman senatorial classes asked for the suspension of the land tax until the end of the war with the Mauri. If Honorius had been in her place, the problem would have been solved with a massacre of Senators, but Galla Placidia was of a completely different nature, so, put under pressure, she had to give in to the request. This decision, however, risked putting the imperial coffers in crisis: to avoid disaster, in February 424, Galla Placidia issued a new loan, with the same conditions as that of her half-brother. Given the excellent performance, the very rich Roman senatorial families joined en masse: so Ravenna was further indebted to them.

[1] Inspired by Silvia Cugini's climate and economic models

[2] The source is the handouts that a colleague of mine distributes for free to his students, before the magnificent rector skins him alive!

[3] The state warehouses where tax revenues were stored

[4] Large estates, cities and parts of the territory

[5] villages

[6] I know it's not boring, but economics helps to understand the functioning of the empire, its evolutions and the choices of Galla Placidia (in fact everything is very similar, except for the role of the Mauri compared to the Vandals, to what happens OTL )

[7] Citizen tax archives

[8] Inspired by an article by William Puppinato

[9] Obviously, the Corippus poem, ITL is very different from the original

[10] Inspired by the rashidun army with some modifications and additions

[11] Inspired by an article by Saverio Gatti

If for the imperial court of Ravenna the phenomenon of climate change may have been very unclear, beyond the rhetorical complaints of "the sun warms less than in the past" and "the winter days are increasingly longer", its effects on Mediterranean agriculture were evident. The lower evaporation was in fact changing the rainfall regime, with drier summers and rainfall essentially concentrated between January and March. Therefore, to be efficient, agriculture was beginning to require significant investments in hydraulic works, capable of exploiting both surface water and aquifers, favoring large senatorial-owned estates over small farmers. Phenomenon that was changing the agricultural landscape in Sicily, Sardinia and Calabria. Forestry, with the production of pitch, the breeding of pigs, the cultivation of vines and fruit trees were progressively replaced by sheep breeding and the production of oil and wheat. [1]

The greatest impact, however, was being had in the African provinces, which from 324, the year in which its taxpayers who already bore the brunt of Rome's ration supply in terms of contributed quantities of oil and grain and liturgical services, was saddled with the burden of paying the wheat contribution previously provided by Egypt, for the distributions of Rome, Mediolanum to which, at the time of Honorius, those for Ravenna were also added

But how significant was this wheat contribution? This topic is very divisive for scholars of the late ancient and early Christian ages. They range from maximalist theses dating back to J. Beloch's idea according to which the royalties, and in particular the wheat rent, were sufficient to satisfy the fundamental needs of the imperial capitals, up to hyperminimalist theses which understand the rent as the exclusive contribution of a plebeian extremely reduced rations: a few tens of thousands of rations. Currently, but things could also change in the coming years, a sort of "moderate minimalism" predominates: scholars believe that the late antique canons were intended to essentially cover the needs of the ration plebs, estimated in the 5th century, considering Rome, Mediolanum and Ravenna , in approximately 250,000 beneficiaries, while the smaller quotas, in particular of wheat and wine, were used for public payments, or poured into circulation at a free price, or used during food supply emergencies. Instead, they tend to exclude, also due to the economic interests of the senatorial class, the existence of regular circuits of foodstuffs sold at political prices coexisting with free distributions, which are not attested either in Rome, Mediolanum and Ravenna, or in Constantinople. In any case, there is no doubt that, in normal situations, the fees calmed the market of fundamental commodities and constituted an indispensable support for a significant part of the population of the imperial capitals. For wheat in particular, considering the diet and calorie needs of an adult, it is reasonable to double the real number of beneficiaries. [2]

The greater fiscal burden, in the face of the decrease in agricultural productivity, as well as increasing the discontent of the African subjects, led the Empire, between the 4th and 5th centuries, to impose a sort of militarization in the collection of wheat rents: according to the agronomist Palladius, in the African regions the peak of the wheat season began at the end of June and ended in July, while the harvest of oil production was concentrated in November. The tributary calendar spanned two solar years with a variable start between the different areas of the empire: July 1st in Egypt, September 1st in other provinces. In Africa the fiscal year ran from November to October and, starting from 364-365, was divided into four months: November-February, March-June, July-October. so, as a rule, taxpayers could deliver the species annonariae to the fiscal horrea of their district in a single solution or in three solutions, with the obligation to pay at least 1/3 of the amount due after the calends of March (evidently to collect the 'new oil) and the rest after the calends of July (evidently to capture the new wheat). for emphyteutic funds the fiscal year began in January and the first payment, also due after the calends of March (and therefore important for oil), was 1/660.

These deadlines seem to reflect an organization of fiscal perception tending to guarantee a continuous flow of foodstuffs and to maximize the receptivity of the ration horrea network by distributing the delivery throughout the year and implementing a rapid movement of the stocks leaving the smaller warehouses towards the larger warehouses . Since the role of local authorities is fundamental for this aspect, two clarifications are appropriate. The laws hinge the provincial collection in the cities' horrea fiscalia, [3]reserved for the exclusive use of the state, which centralized perception. In fact, the first phase of the collection, carried out by praepositi pagorum et horreorum appointed by the curiae, also took place, and perhaps to a primary extent, in warehouses distributed throughout the territory from which the foodstuffs were subsequently transferred to the cities. This method is evident in the instructions of the epigraphic constitution of Trinitapolis of Valentinian I, specifically referring to southern Italy but adhering to regulations of general scope. And in fact also in the "Tariff of Carthage", referring to the proconsular and attributable to the emperor himself, the toponyms of 27 tax districts bear three different names: fundi, civitates, pars territoriali [4] (the latter term perhaps to be understood as equivalent to pagus)[5]. It is also not excluded that, for reasons of logistical convenience, in some locations the perception took place at the stations close to the coast and that therefore these loads were not forwarded from the territory to the city but taken directly to the ports of embarkation. This reconstruction is supported by general provisions on the obligation of the presence of sample measurements in the stations [6]

Obviously, Honorius, with his passion for micro management, could not fail to have his say in such an organization: he introduced the institution of tax quarters and quarterly payments (tripartita inlatio), payment receipts that the taxpayer had to forward to the municipal tabularii [7]and a series of rather punitive measures against tax evaders and officials who stole part of the grain and other commodities: in the best case scenario, they would end up working in the Sardinian mines for life, in the worst case, well, Honorius had vented his anger in penis several sadistic fantasies!